9 Bending Loads

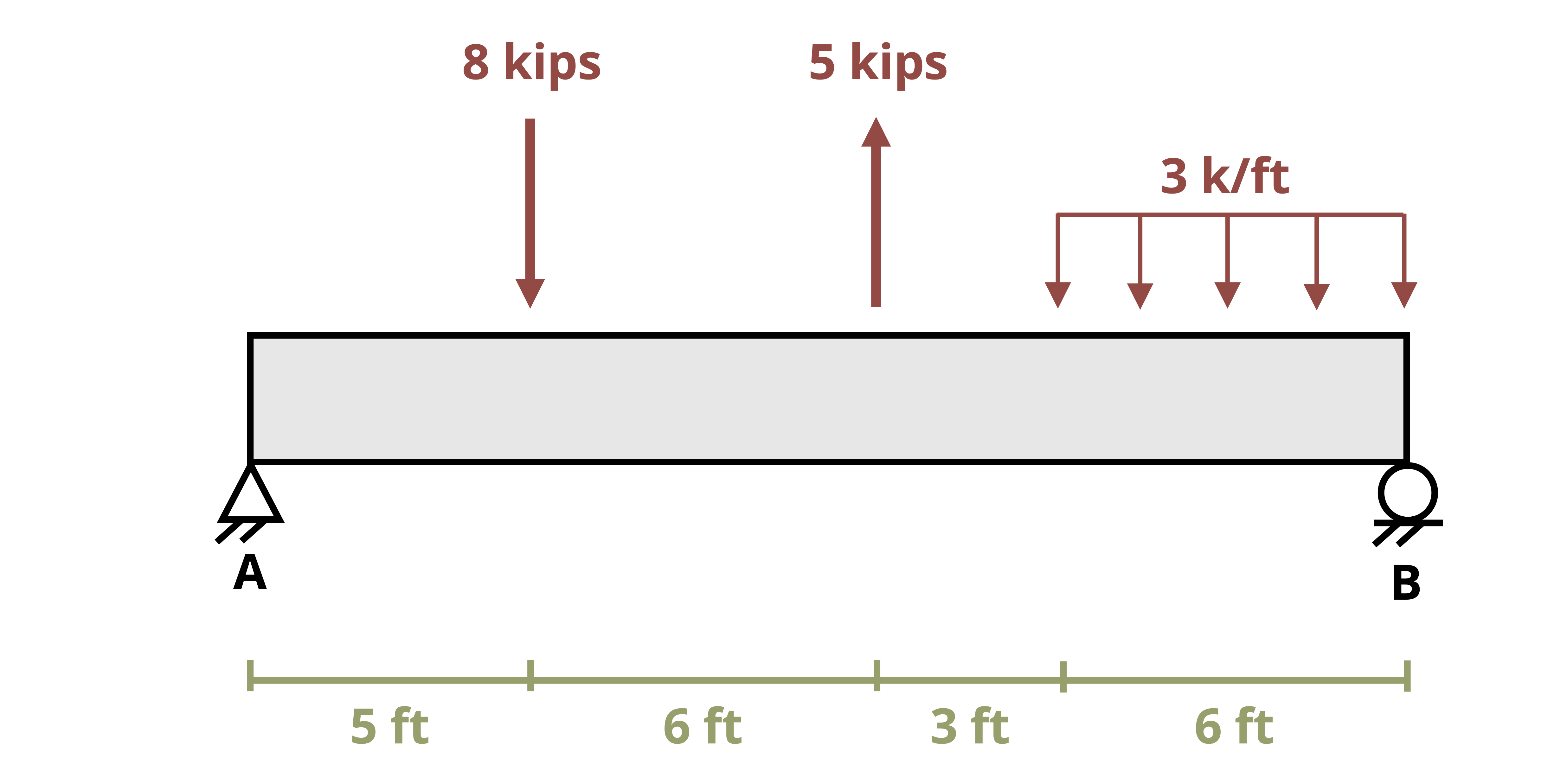

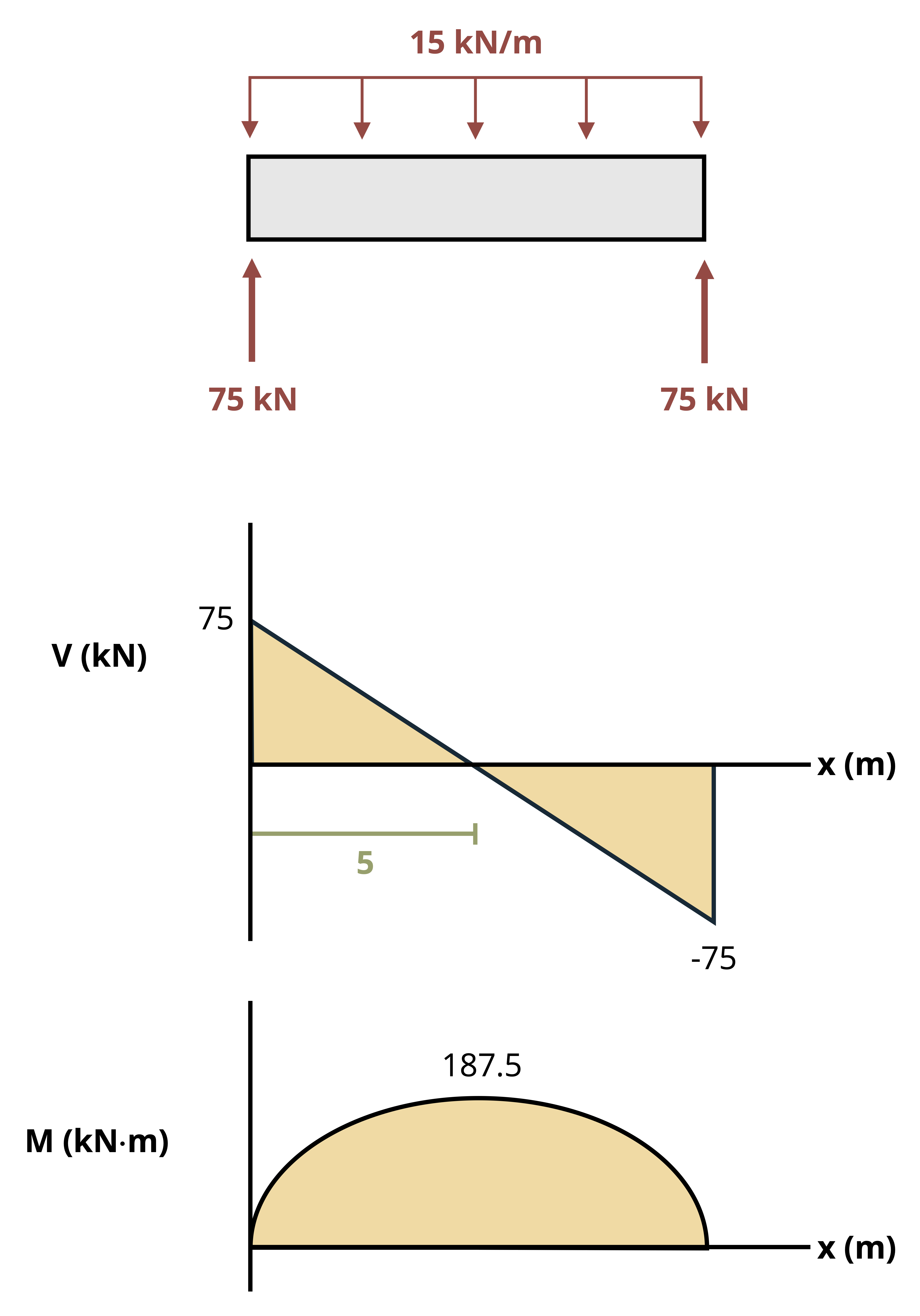

Beams are structural members that support loads along their length. Typically these loads are perpendicular to the axis of the beam and cause only shear forces and bending moments.

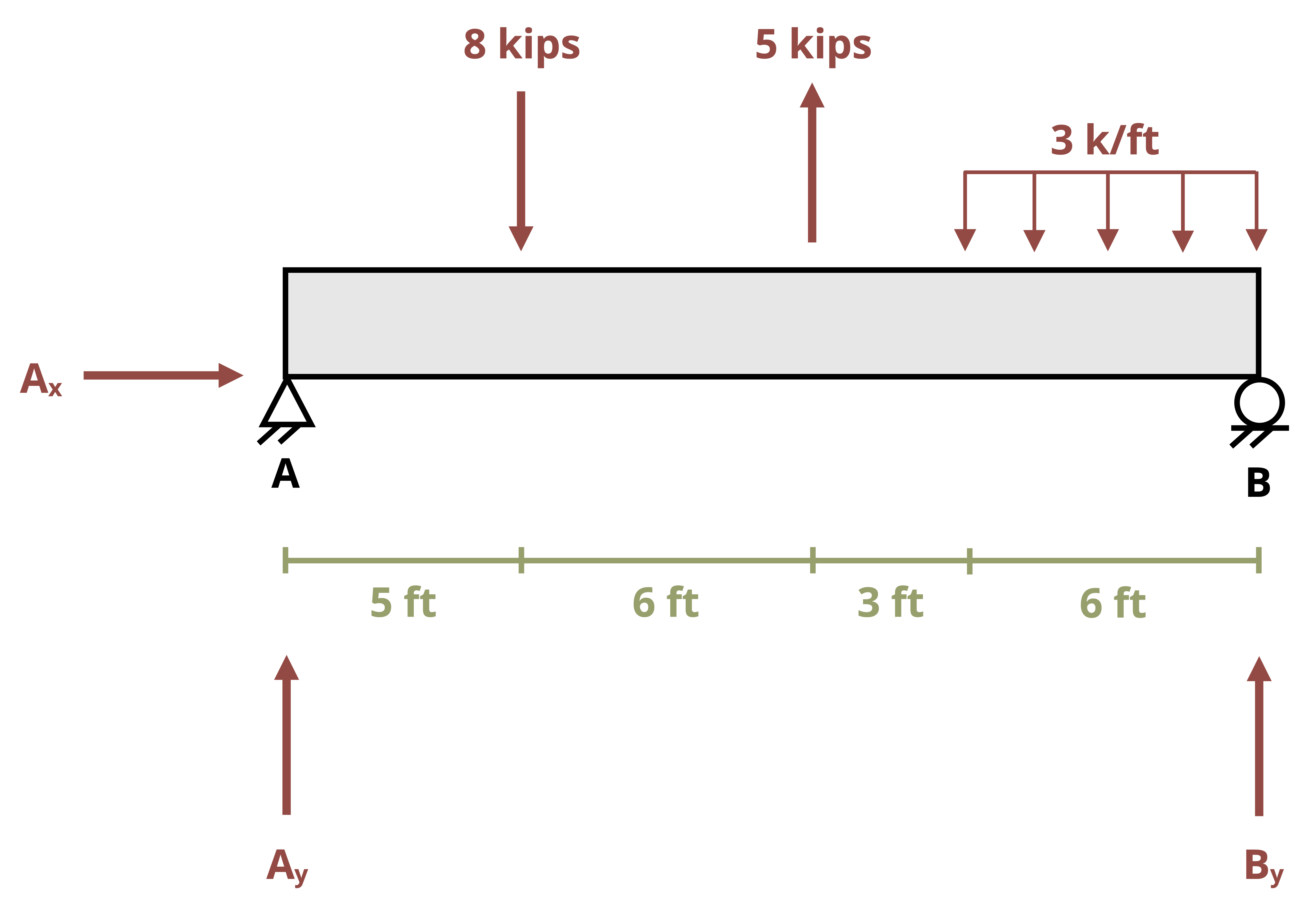

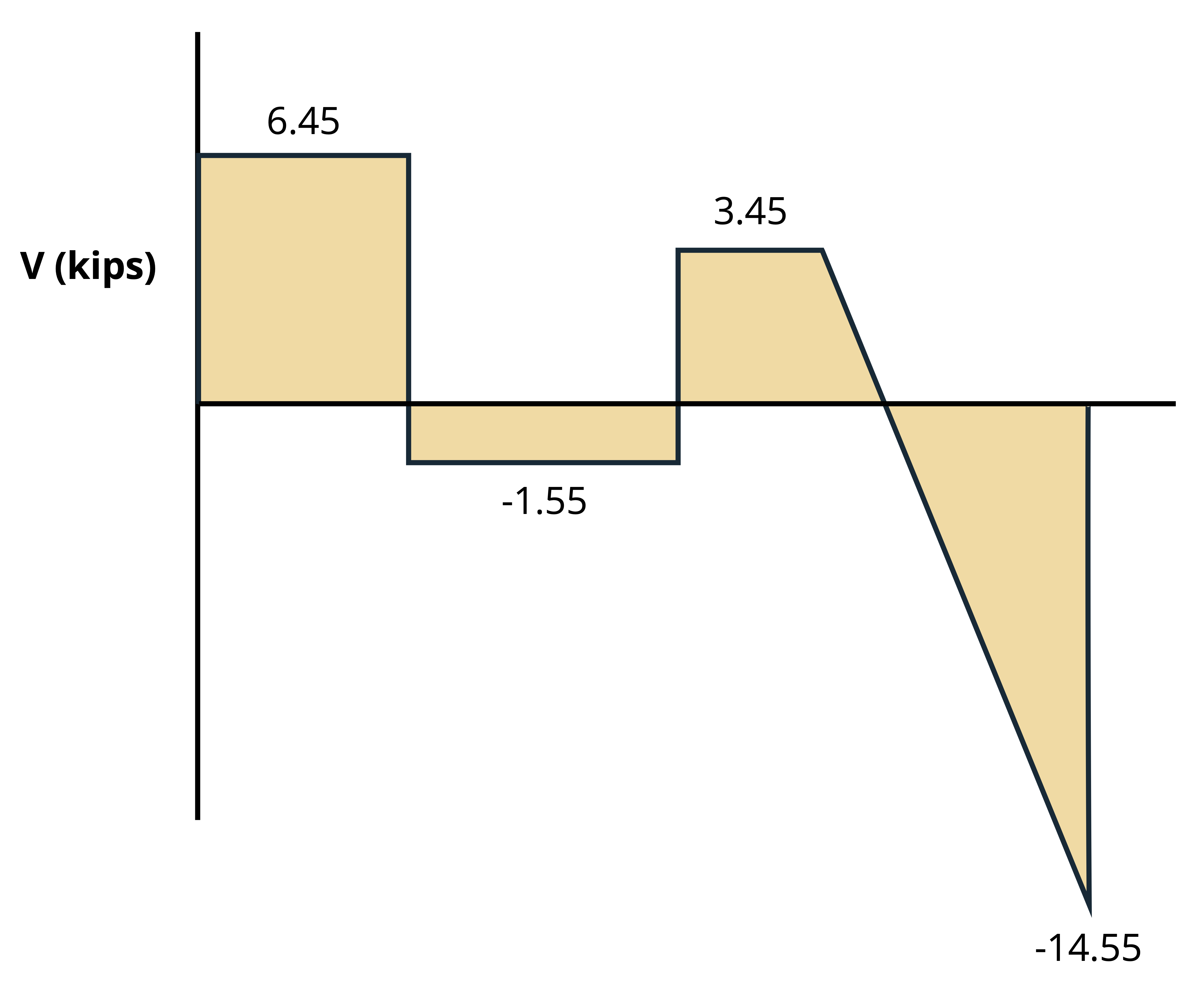

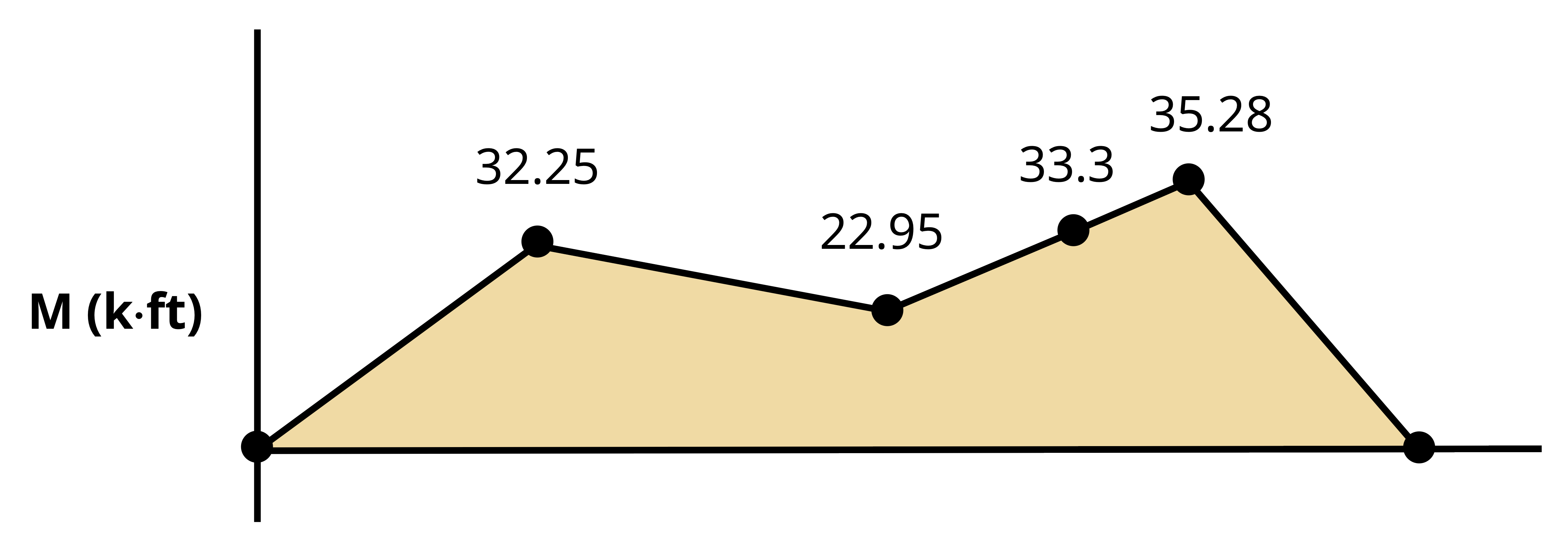

As discussed in previous chapters, internal forces and moments and section properties are crucial to calculating stresses and deflections. The same is true for finding stresses and deflections in beams. This chapter describes calculating bending stresses in beams, such as those in Figure 9.1, with considerations for unsymmetric bending and beam design.

Section 9.1 derives an equation for calculating bending stress. Section 9.2 discusses how to design beams to ensure they don’t fail due to bending stress. Section 9.3 extends the analysis to include cases where the bending moment not only acts about the horizontal axis of the beam but has components about both the horizontal and the vertical axes.

9.1 Bending Stress

Click to expand

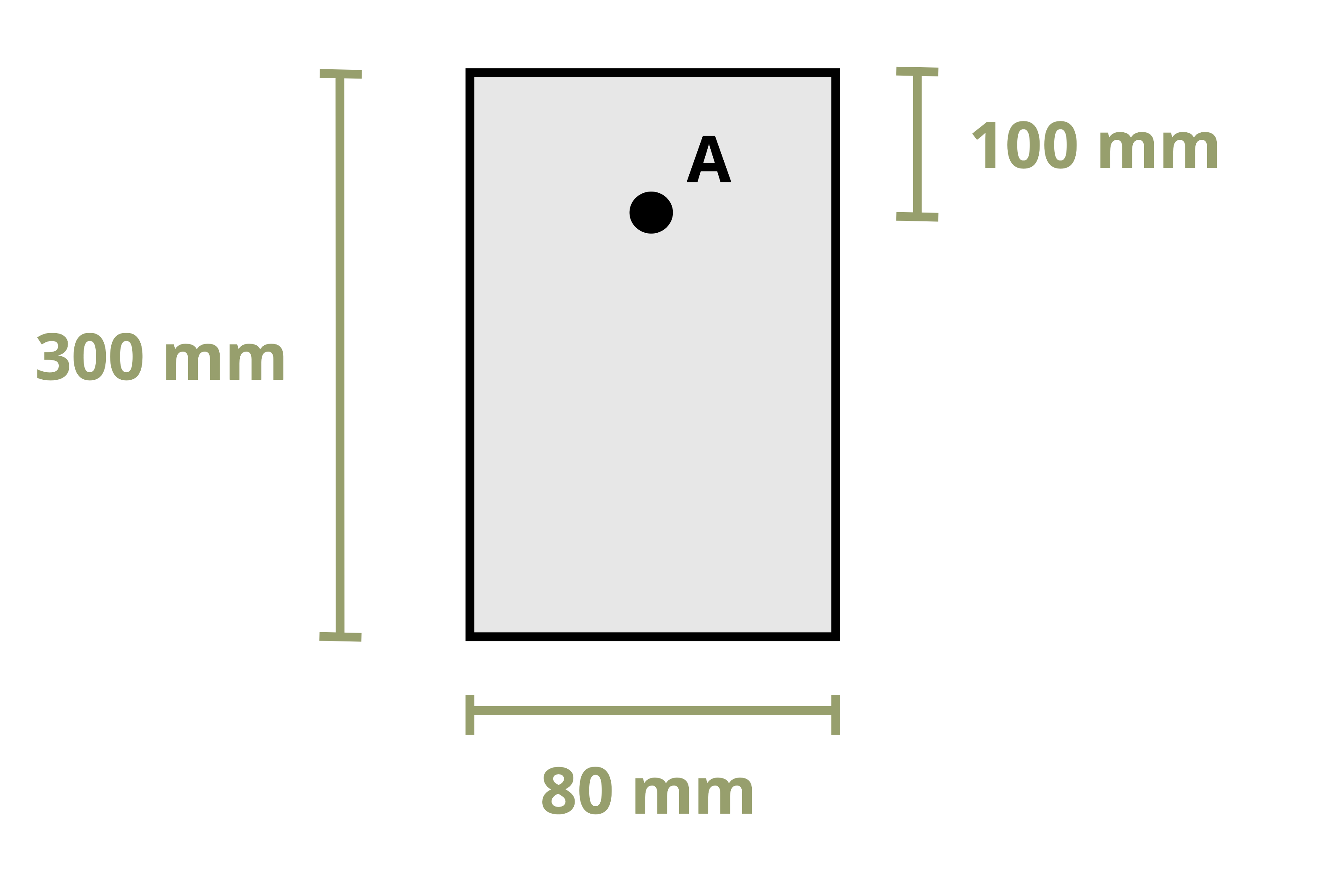

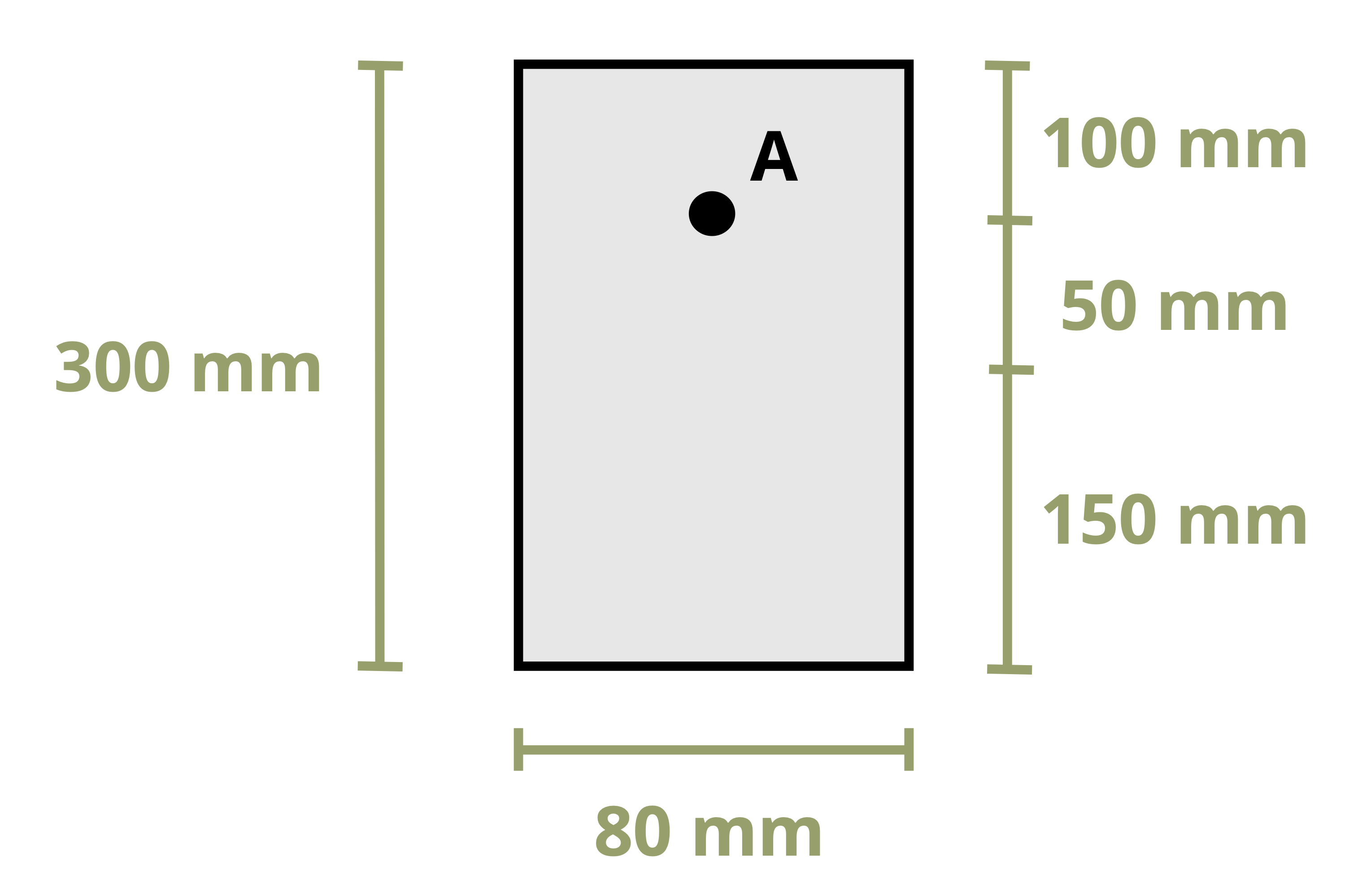

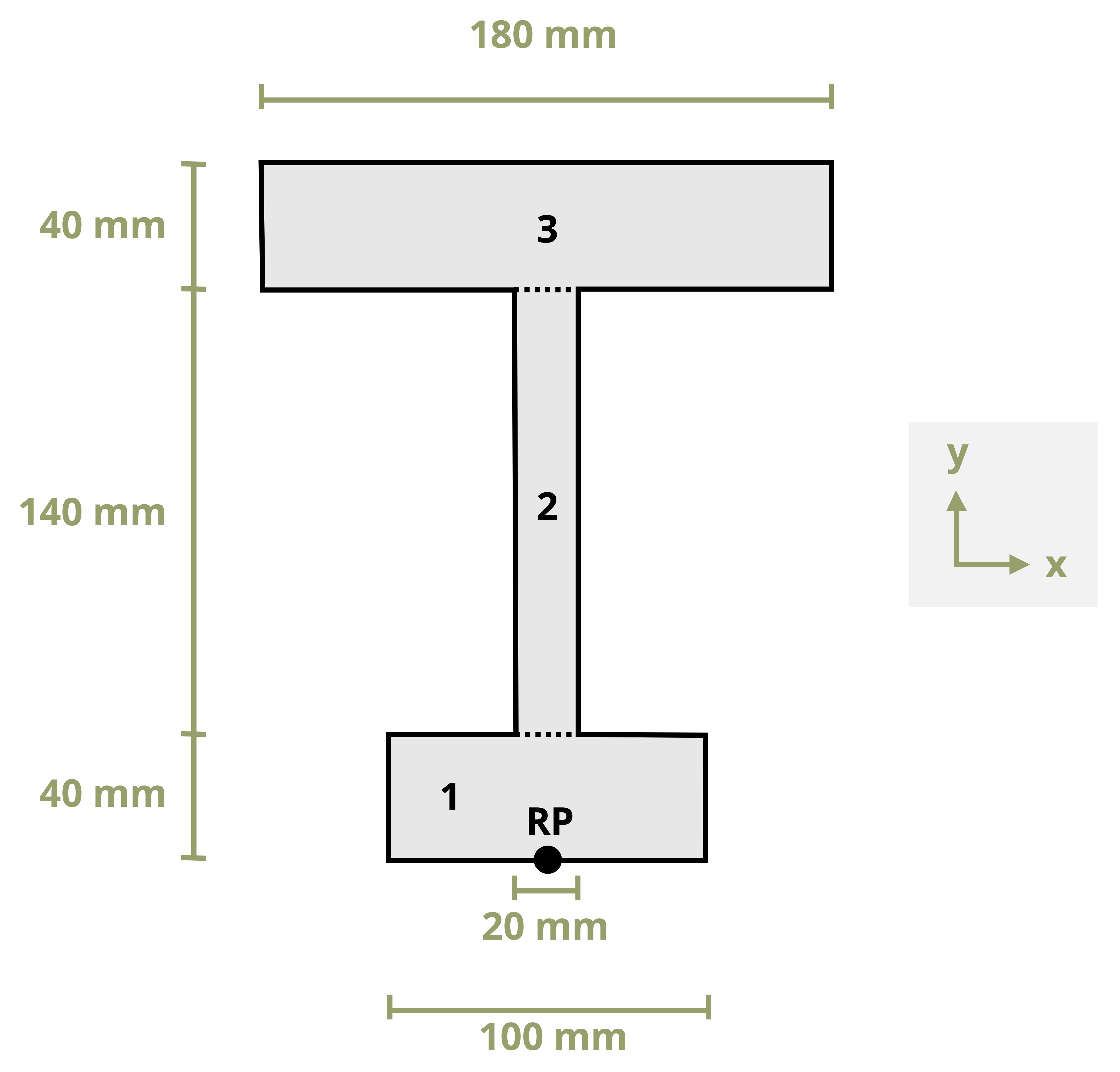

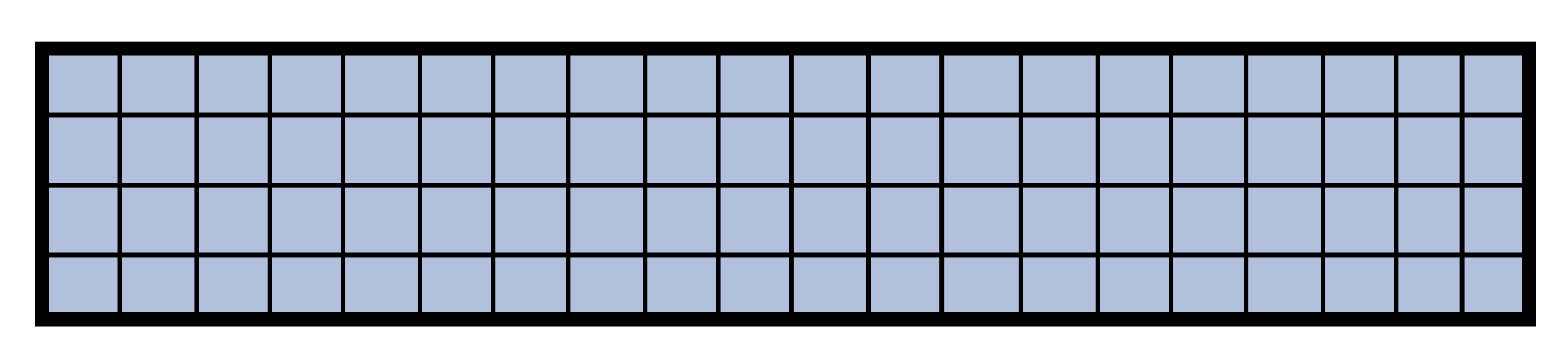

This section discusses bending behavior of straight, symmetric, homogeneous beams. Additionally, this section is limited to beams with a cross section that is symmetric with an axis and whose bending moment is around an axis that is perpendicular to the axis of symmetry. Examine the initially unaltered beam depicted in Figure 9.2, which is characterized by a rectangular cross-section and annotated with both horizontal and vertical grid lines.

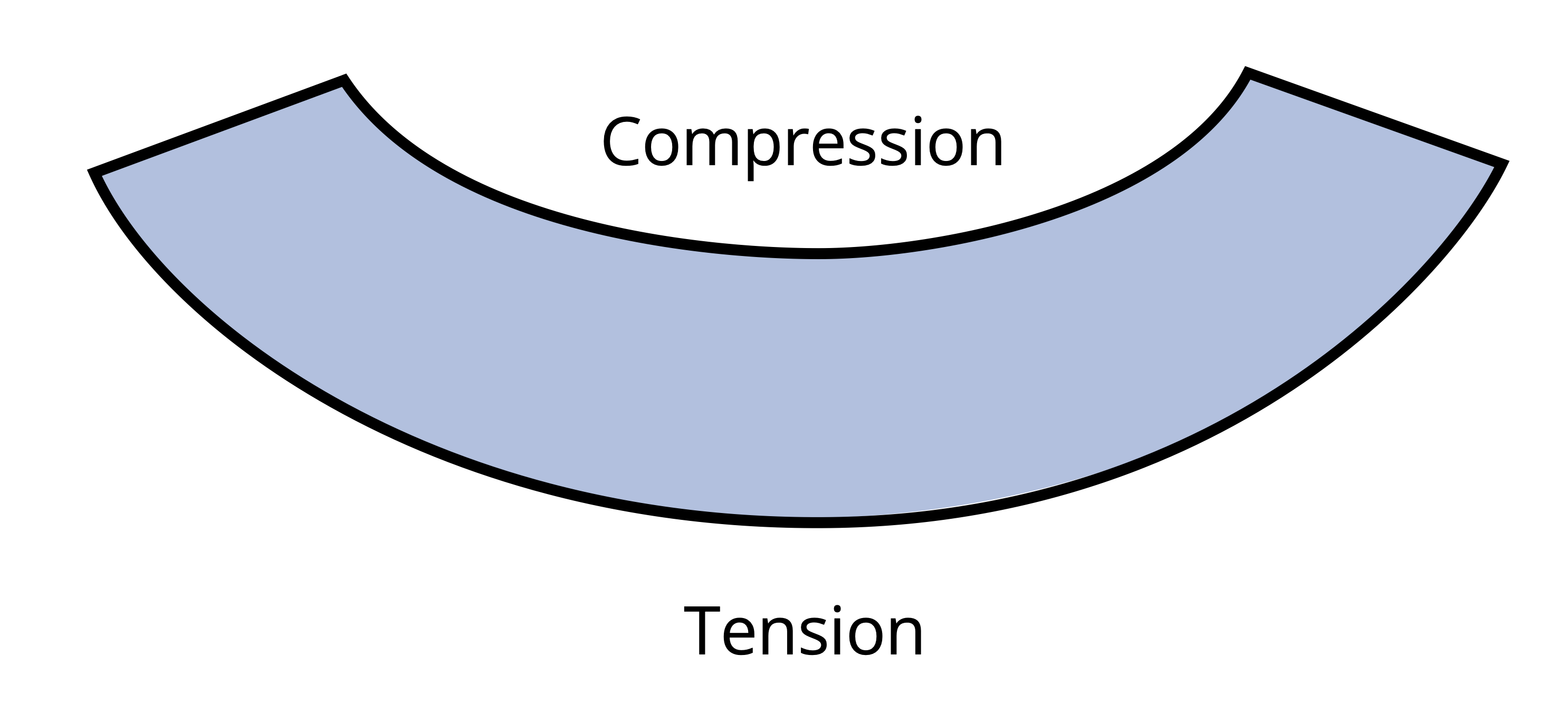

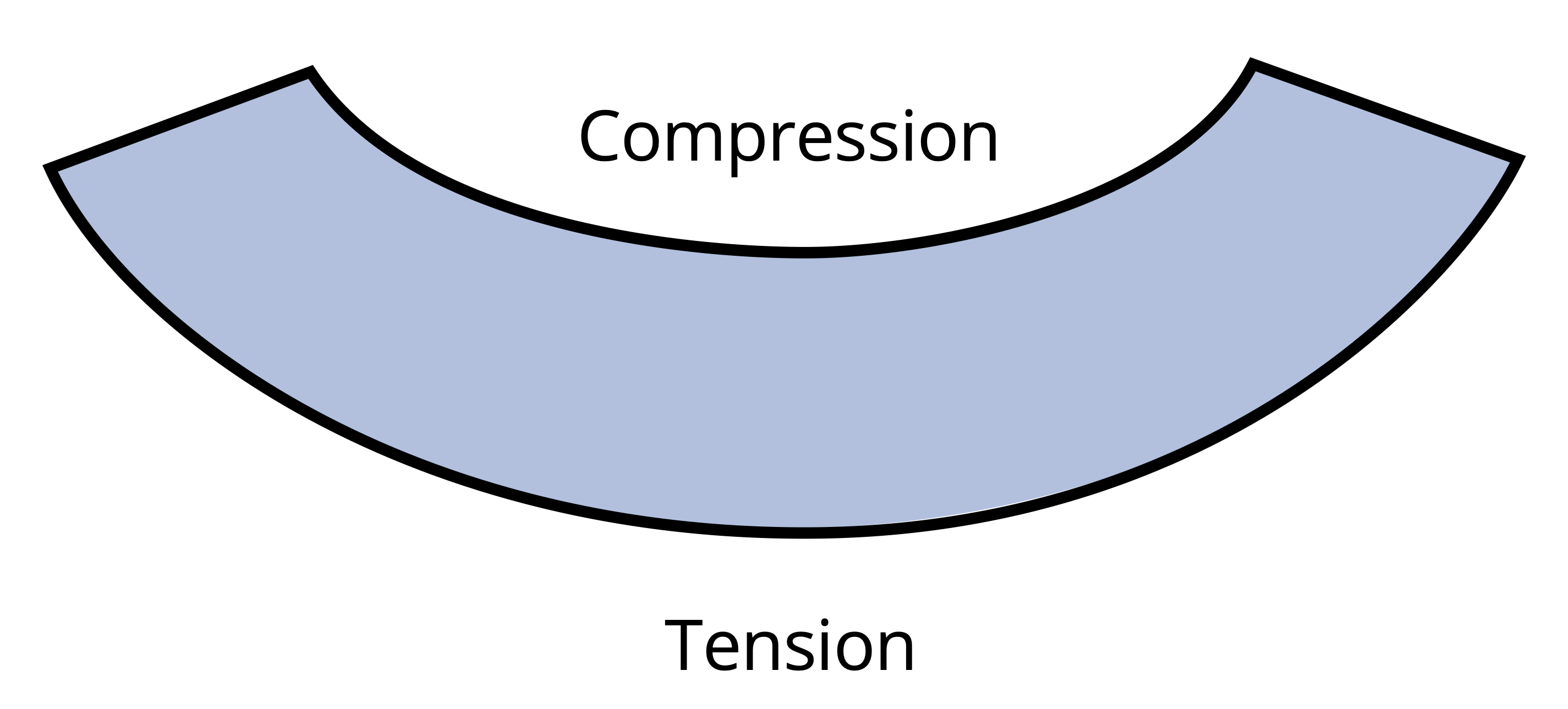

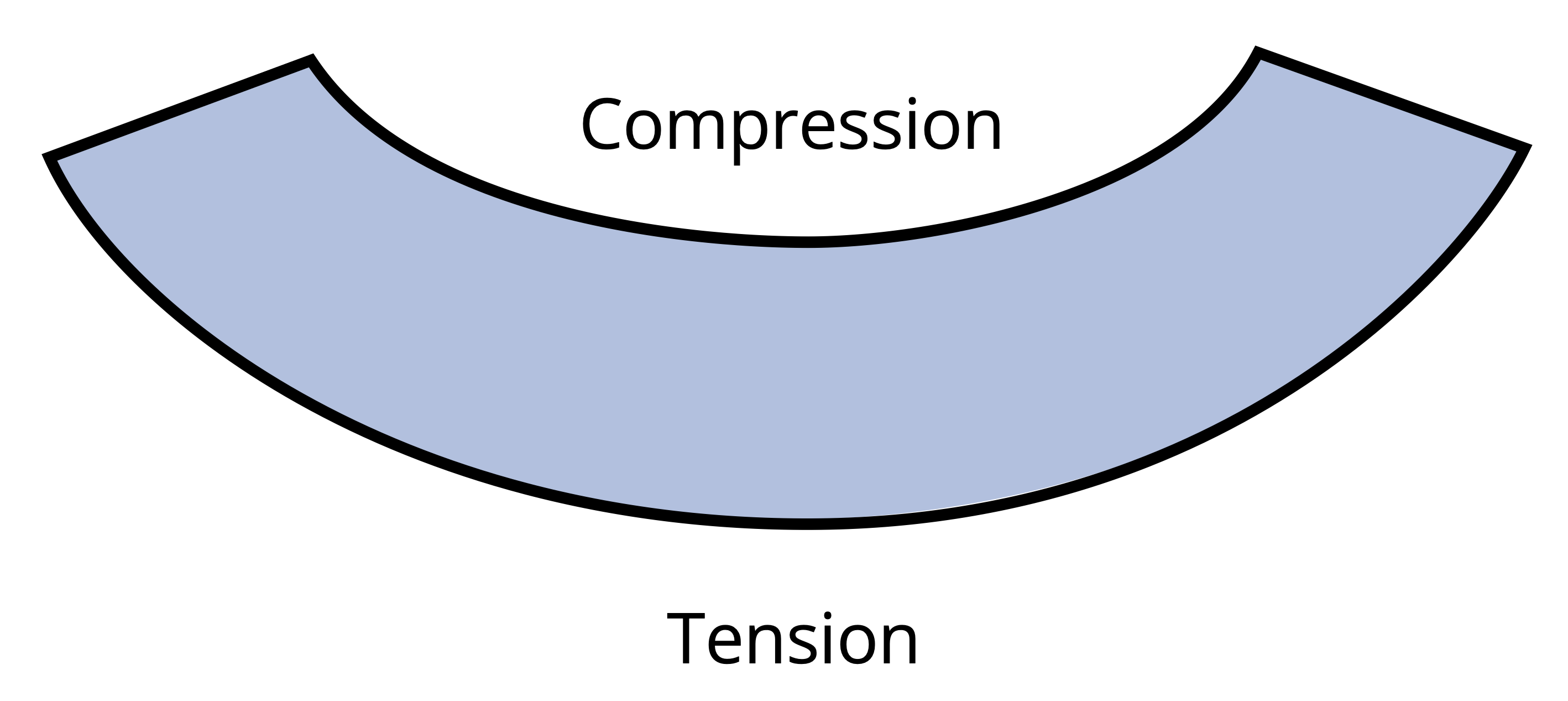

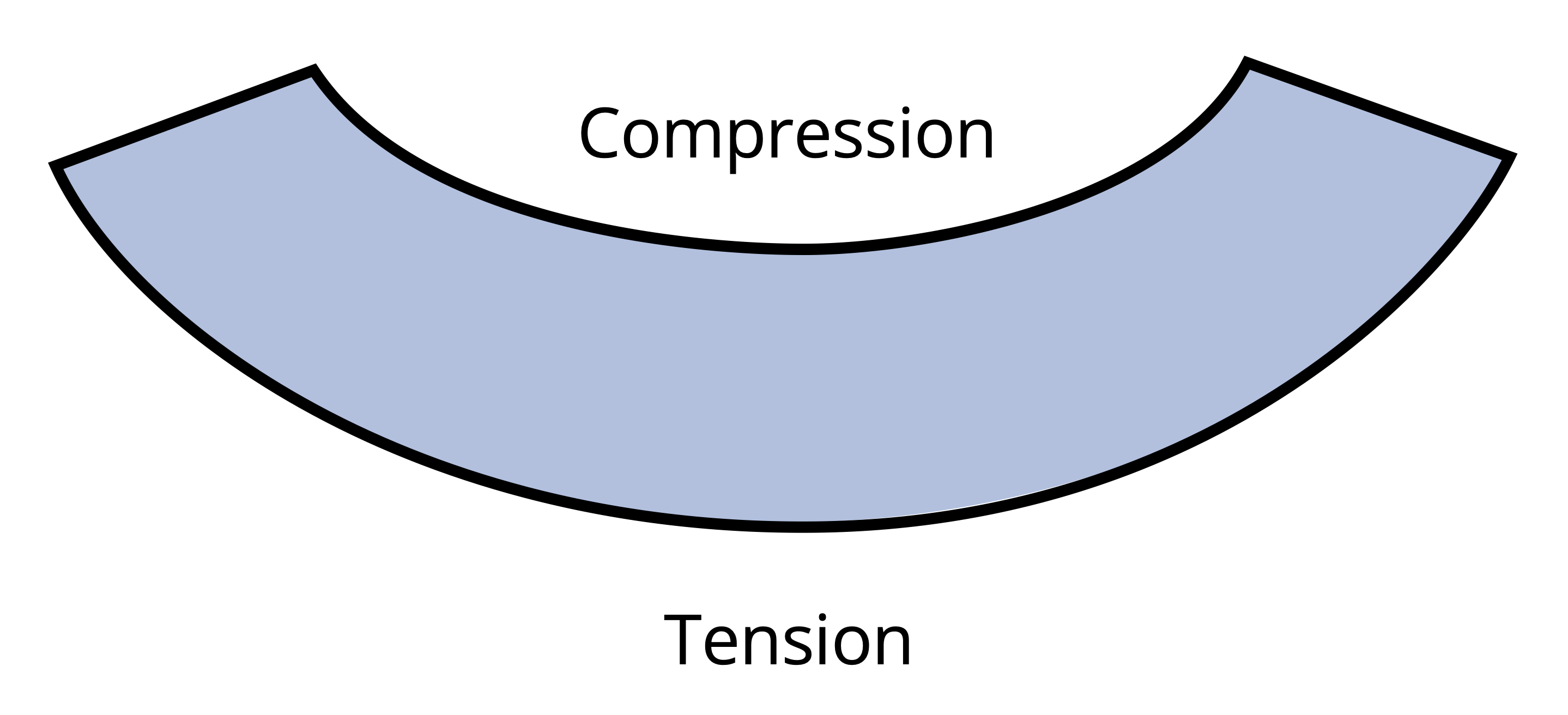

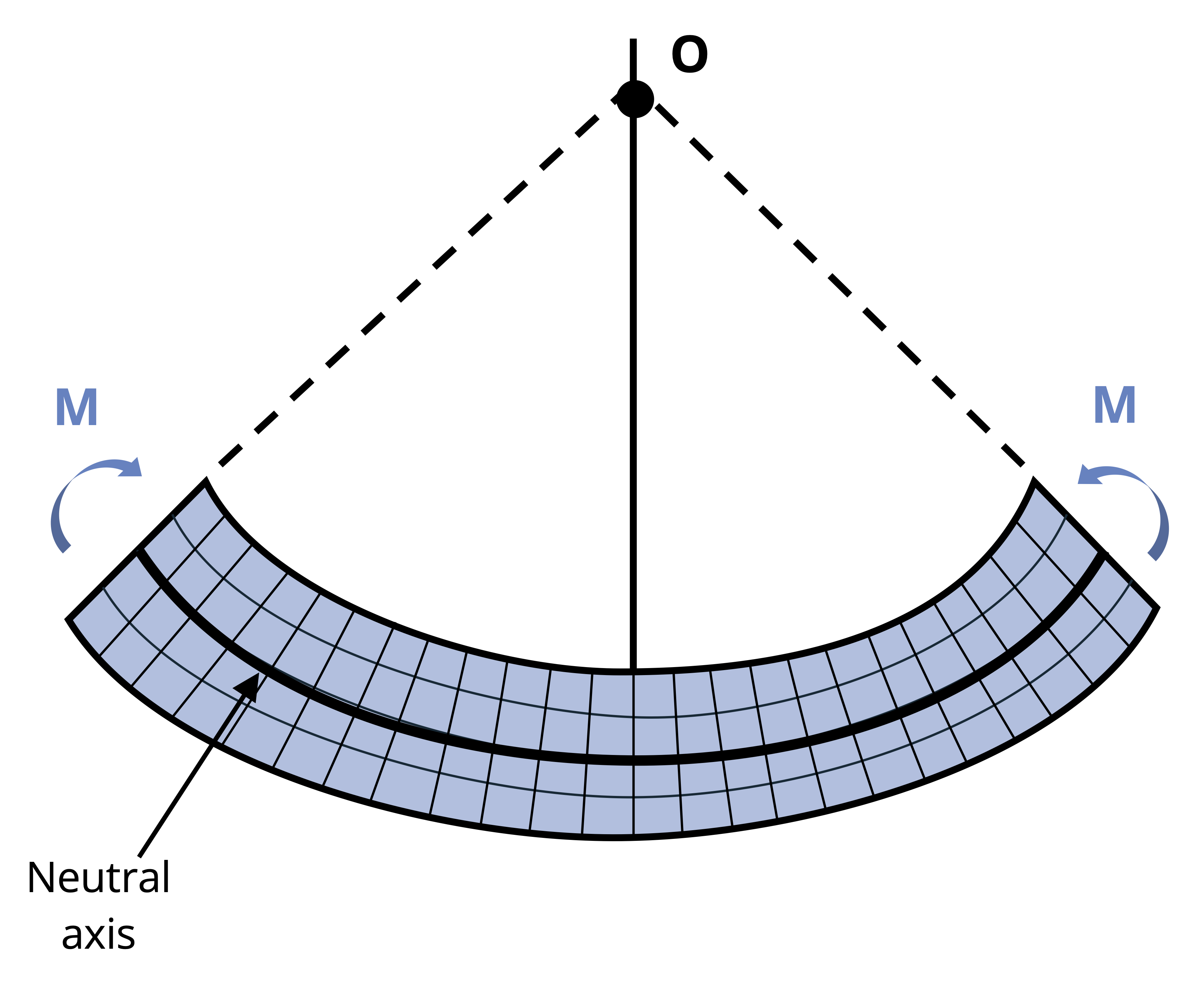

When a bending moment is applied, horizontal lines curve, whereas vertical lines remain straight but rotate, as illustrated in Figure 9.3. The material stretches at the bottom and compresses at the top, creating a neutral surface in between where fibers experience no length change. On a cross-section this surface appears as the neutral axis.

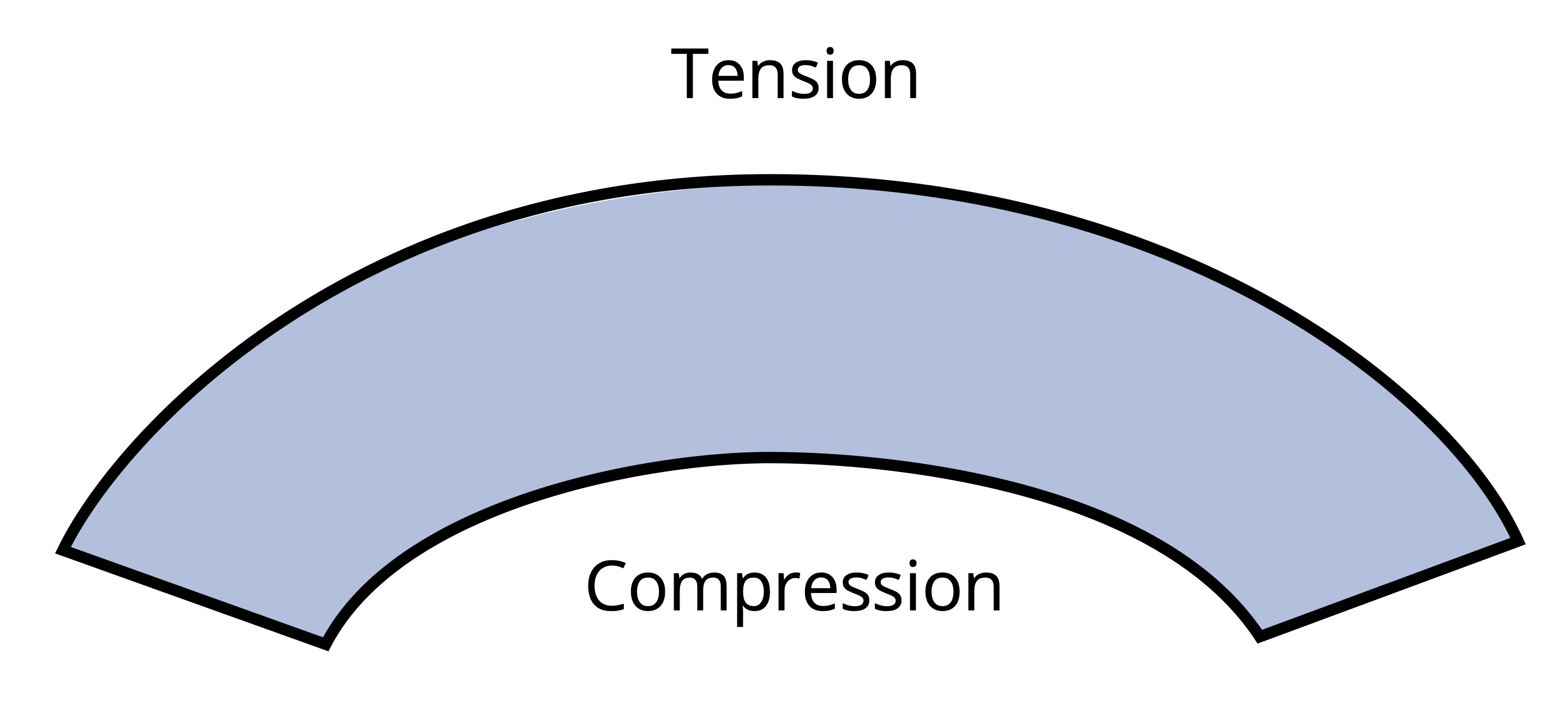

We can make a similar observation when a kid’s toy undergoes bending as shown in Figure 9.4. This toy is subjected to a bending moment in the opposite direction of the beam depicted in Figure 9.3, and this direction switches the behavior of the top and the bottom surfaces. Notice in Figure 9.4 that the fibers at the top are pulled apart whereas the bottom surface fibers are pushed together.

This knowledge about deformations due to bending can be applied to the failure of the column in Figure 9.5. Notice that the column was fixed at the base and subjected to a transverse force that caused failure. The fibers on the right side of the column failure point were pulled apart, whereas the fibers on the left side of the column failure point were compressed.

We make the following assumptions about deformations due to bending:

There must be a neutral surface parallel to both the upper and lower surfaces, where the length remains constant.

Throughout the deformation all cross sections of the beam remain plane and perpendicular to the longitudinal axis.

The cross section will keep its shape (we’ll ignore the Poisson effects discussed in Section 4.4 of this text).

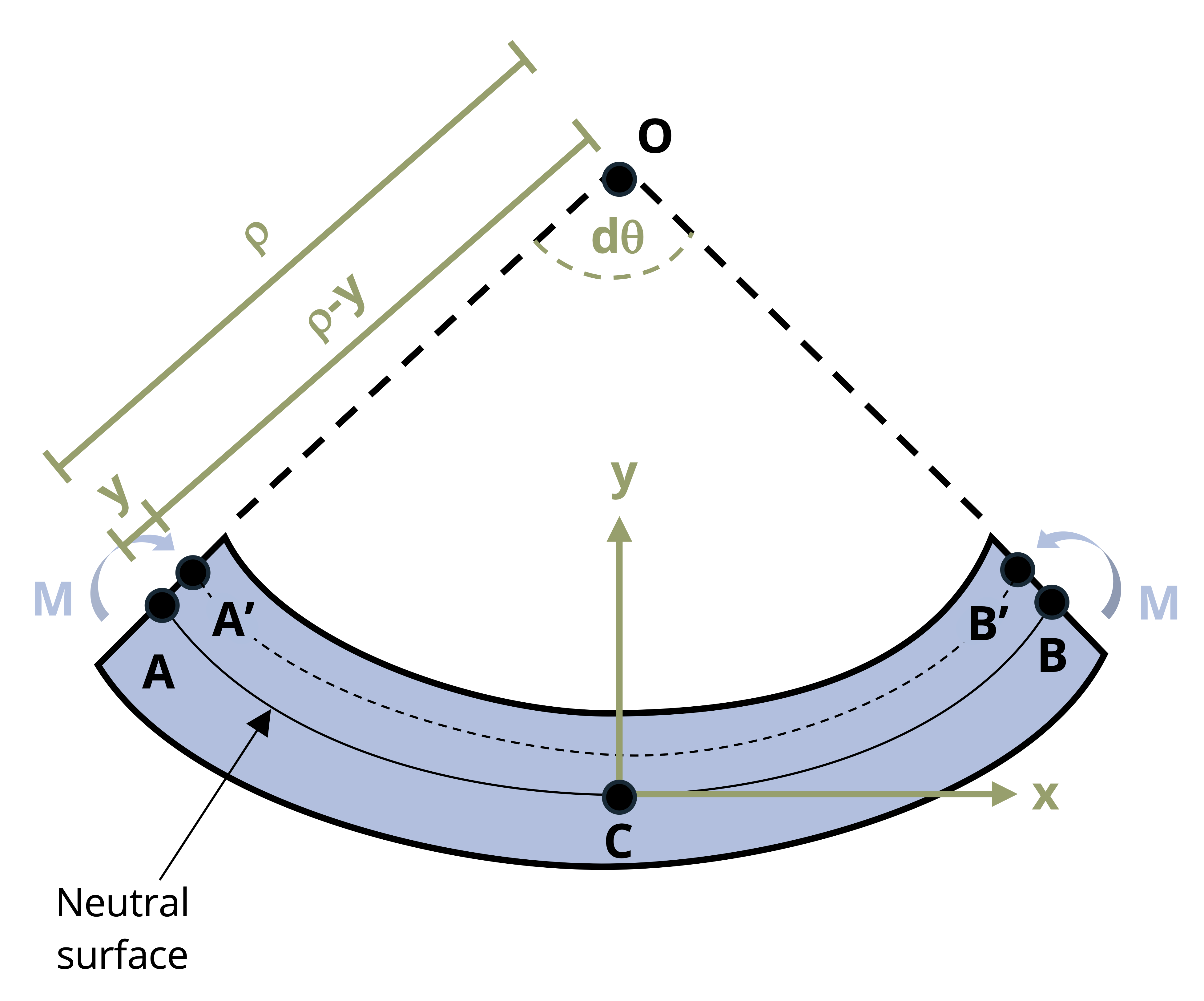

To understand bending stress in a beam subjected to arbitrary loads, examine a small element extracted from the beam as shown in Figure 9.6. The derivation of the bending strain equation remains unaffected by the beam type or specific loads. Remember the fundamental definition of normal strain is

\[ \varepsilon=\frac{\Delta L}{L}\text{ .} \]

This equation can be used to calculate the normal strain along AB in the beam.

\[ \varepsilon=\frac{\overline{A^{\prime} B^{\prime}}-\overline{A B}}{\overline{A B}} \]

Distance y is measured relative to the neutral surface and is positive above the neutral surface and negative below. Before bending, line AB is the same length at all y values. During bending, though, line A’B’ shortens above the neutral surface and lengthens below it. By definition the length of the neutral surface doesn’t change and remains the same as length AB. The lengths AB and A’B’ can be described using the radius of curvature (ρ) and the differential angle (dθ) shown in Figure 9.6.

\[ \begin{gathered} \overline{A B}=\rho d \theta \\ \overline{A^{\prime} B^{\prime}}=(\rho-y) d \theta \end{gathered} \]

Now we substitute these lengths into the strain equation.

\[ \varepsilon=\frac{(\rho-y) d \theta-\rho d \theta}{\rho d \theta} \]

Simplifying the equation yields

\[ \begin{gathered} \varepsilon=\frac{\rho d \theta-y d \theta-\rho d \theta}{\rho d \theta} \\ \varepsilon=\frac{-y d \theta}{\rho d \theta} \\ \varepsilon=-\frac{y}{\rho} \end{gathered} \]

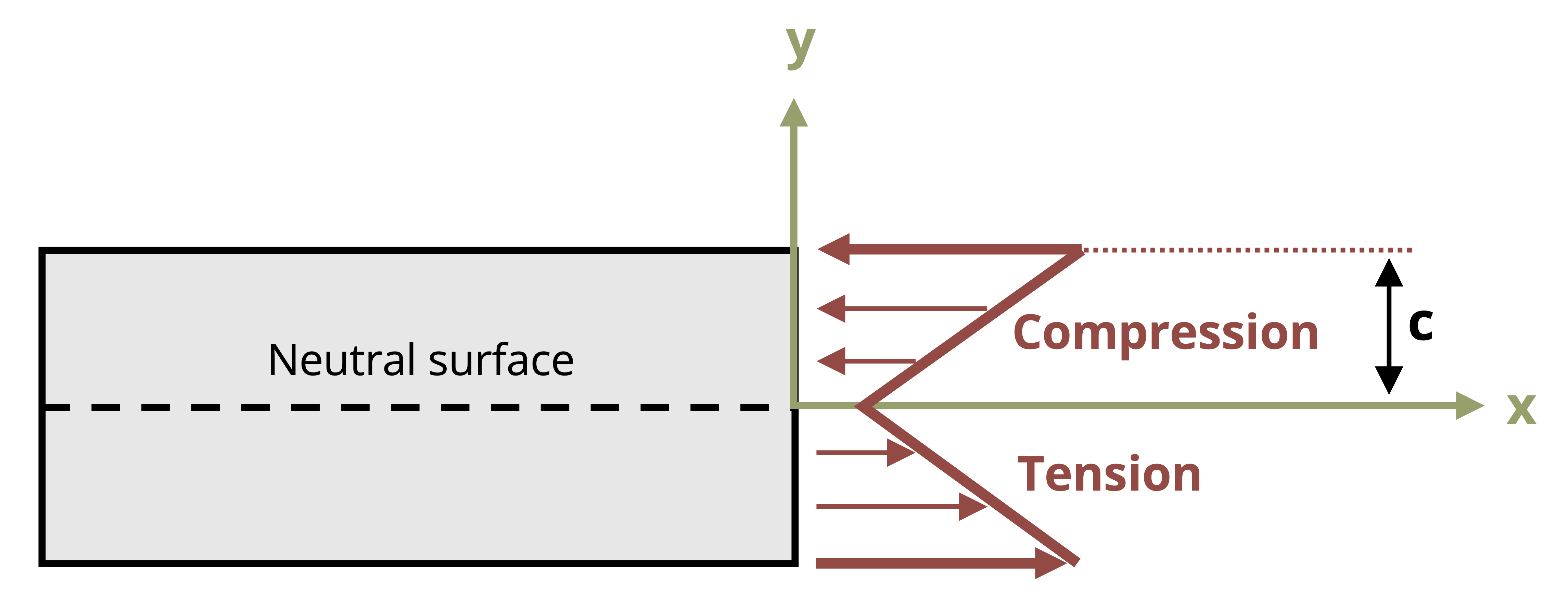

This relationship shows us that the longitudinal strain, ε, varies linearly with the distance, y, from the neutral surface. The maximum stress occurs at the outermost fibers, the extreme top and bottom of the section. This maximum distance from the neutral surface is designated c. A relationship for the maximum absolute value of the strain, εmax can now be calculated.

\[ \begin{gathered} \frac{\varepsilon}{\varepsilon_{\max }}=-\frac{y / \rho}{c / \rho} \\ \varepsilon=-\left(\frac{y}{c}\right) \varepsilon_{\max } \end{gathered} \]

Assuming that the material behaves in a linearly elastic manner, we use Hooke’s law, \(\sigma = E \epsilon\), to rewrite the strain relationship into a relationship of stresses.

\[ \sigma=-\left(\frac{y}{c}\right) \sigma_{\max } \]

Therefore, similar to the variation in normal strain, normal stress, σ, will fluctuate from zero at the neutral surface to a maximum value, σmax, at a distance c from the neutral surface as shown in Figure 9.7.

For us to determine the position of the neutral surface, the resultant force generated by the stress distribution across the cross-sectional area must be equal to zero.

\[ 0=\int_A F_{resultant}=\int_A \sigma d A \]

We can now substitute the previous relationship between stress and distance from neutral axis.

\[ \begin{aligned} & 0=\int_A-\left(\frac{y}{c}\right) \sigma_{\max } d A \\ & 0=-\frac{\sigma_{\max }}{c} \int_A y d A \end{aligned} \]

Since \(-\frac{\sigma_{\max }}{c}\) does not equal zero, what remains is

\[ 0=\int_A y d A \]

This integral represents the first moment of area, as discussed in Section 8.1. This equation indicates that the first moment of the cross-section about its neutral axis must be zero. Recall that the location of the centroid was determined by \(\bar{y}=\frac{\int_A y d A}{A}\). Consequently, for a member experiencing pure bending and as long as the stresses remain within the elastic range, the neutral axis traverses through the centroid of the section because \(\bar{y}\) (the distance from the neutral axis to the centroid) is zero.

The stress in the beam can be ascertained by setting the moment M equal to the moment produced by the stress distribution around the neutral axis.

\[ d M=y d F \]

Since

\[ d F=\sigma d A\text{ ,} \]

we can write

\[ \begin{gathered} M=\int_A y d F=\int_A y(\sigma d A)=\int_A y\left(-\frac{y}{c} \sigma_{\max }\right) d A \\ M=\frac{\sigma_{\max }}{c} \int_A y^2 d A \end{gathered} \]

Note that the integral, \(\int_A y^2 d A\), represents the second moment of area, or the moment of inertia, of the cross-sectional area about the neutral axis. Here second moment of area is denoted with I, as in Section 8.2.

Rearranging the previous equation to obtain the flexure formula yields

\[ \boxed{\sigma_{\max }=\frac{M c}{I}}\text{ ,} \tag{9.1}\]

σmax = Maximum bending stress in the beam; note that a complete description includes magnitude, units, and tension or compression [Pa, psi]

M = Internal bending moment calculated about the neutral axis of the cross section, determined from method of sections or shear and moment diagrams [N·m, lb·in.]

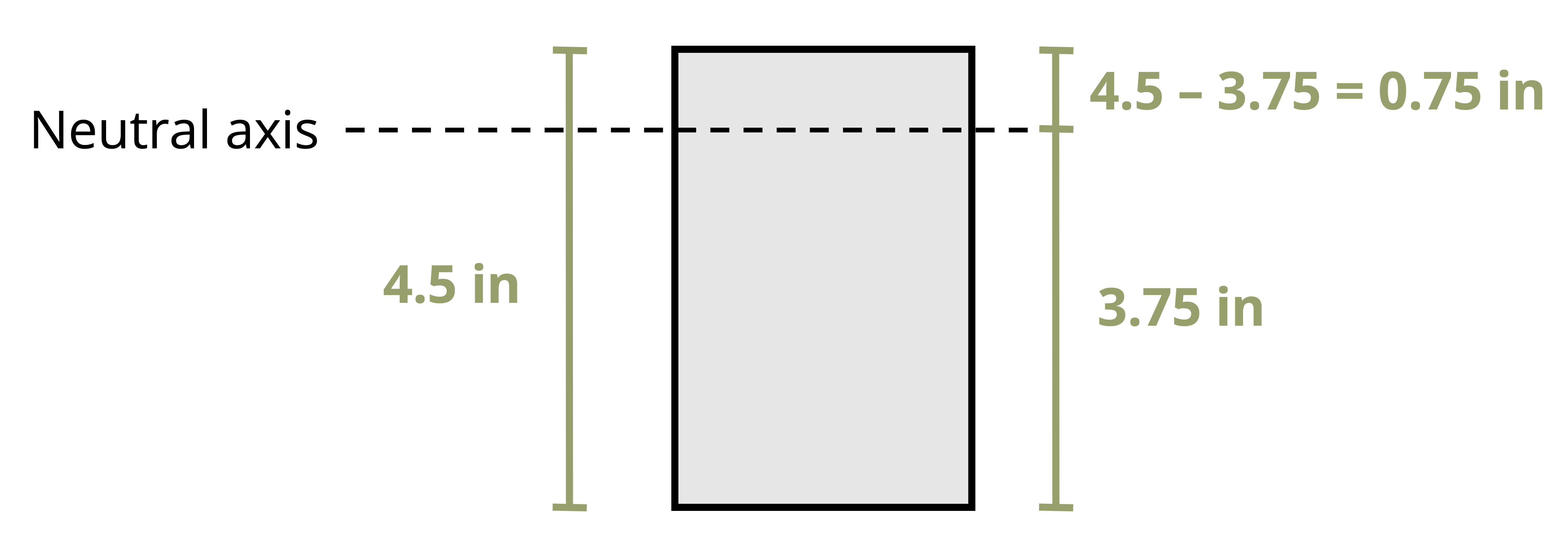

c = Perpendicular distance from the neutral axis to the point farthest from the neutral axis [m, in.]

I = Second moment of area about the neutral axis [m4, in.4]

Previous derivation has shown that

\[ \sigma=-\left(\frac{y}{c}\right) \sigma_{\max } \]

This can be rearranged to provide the following relationship:

\[ \frac{\sigma_{\max }}{c}=-\frac{\sigma}{y} \]

We can determine a similar flexure formula to calculate the bending stress at any point along the cross section.

\[ \boxed{\sigma=-\frac{M y}{I}}\text{ ,} \tag{9.2}\]

σ = Bending stress [Pa, psi]

M = Internal moment calculated about the neutral axis of the cross section [N·m, lb·in.]

y = Perpendicular distance from the neutral axis to the point of interest [m, in.]

I = Second moment of area about the neutral axis [m4, in.4]

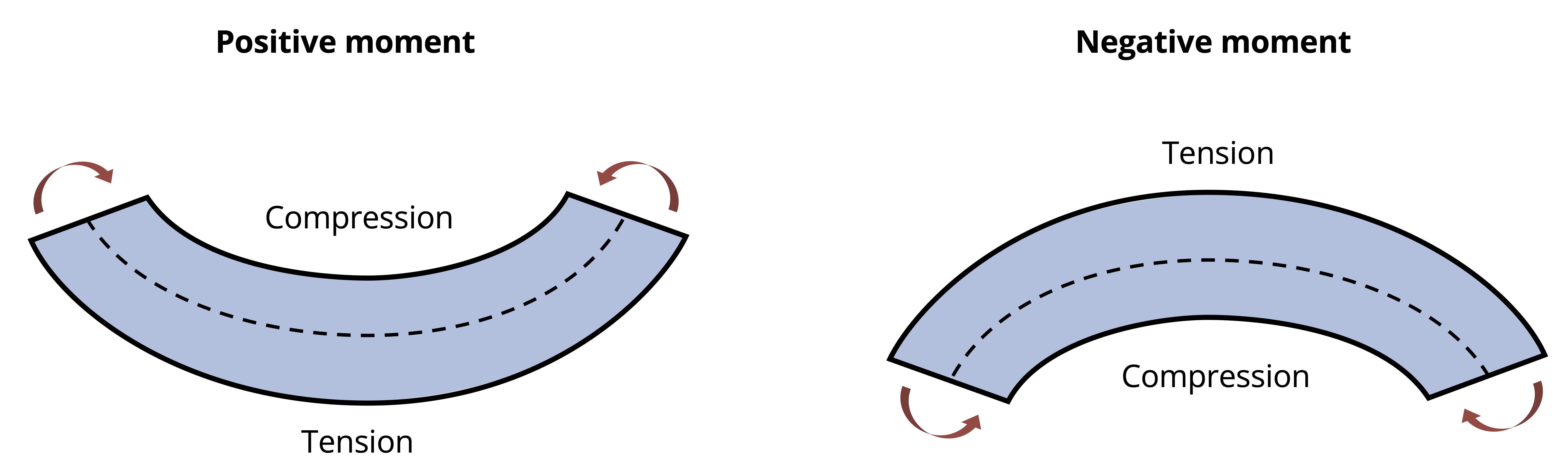

As emphasized in Chapter 2, when reporting normal stress engineers must indicate whether that stress is in tension or compression. The derivation for Equation 9.2 used a beam bending concave upward. In Chapter 7 we indicated that this type of moment was considered positive. This leads to compression above the neutral axis and tension below. The inverse is true when the beam is subjected to negative bending moment as shown in Figure 9.8.

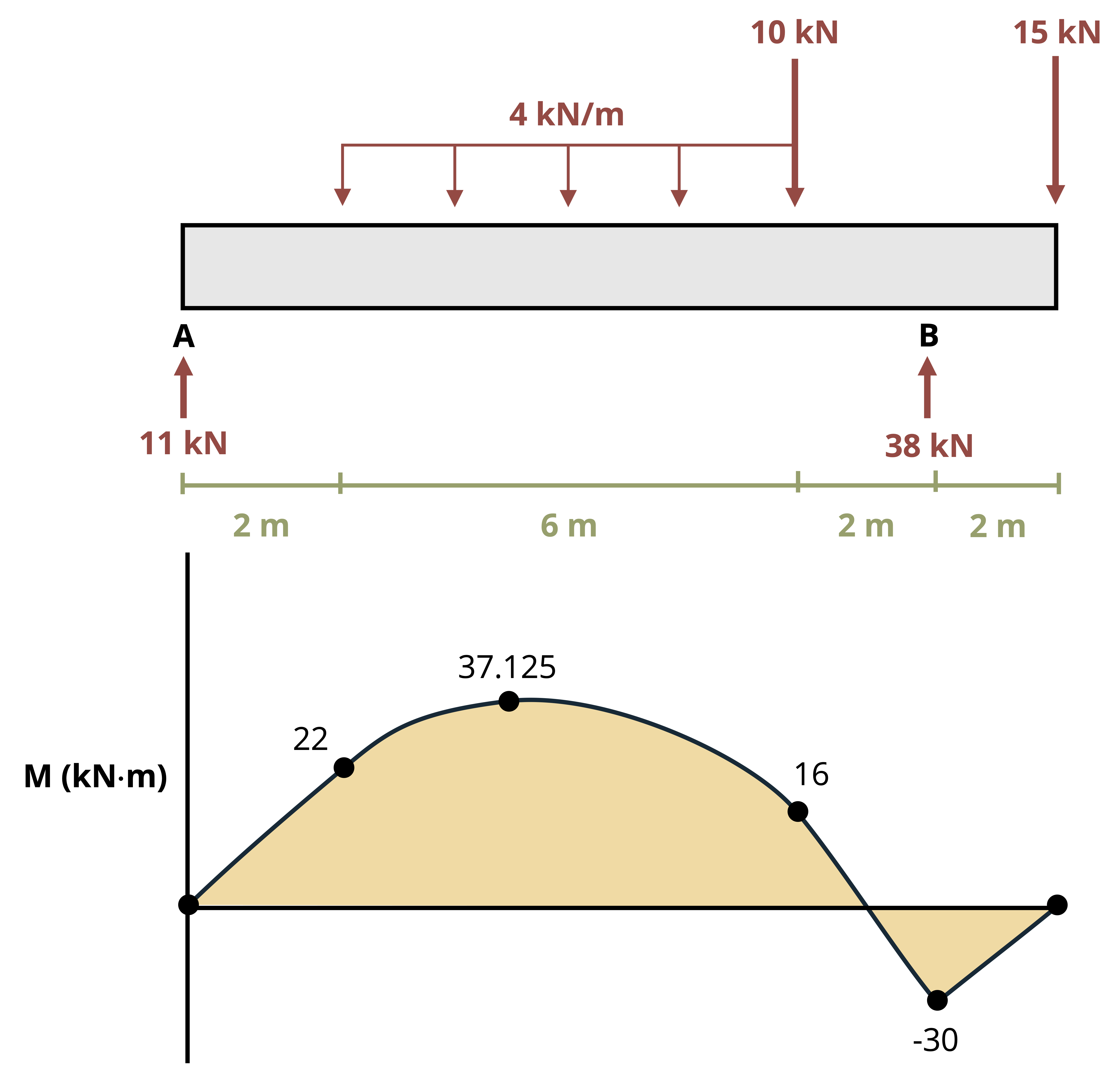

Example 9.2 and Example 9.3 demonstrate the calculation of bending stresses at various points on a cross-section.

For many situations the overall largest stress would be sufficient. However, some materials behave differently depending on whether they are subjected to tensile or compressive stress. Concrete is a good example of this, as it’s relatively strong against compressive stresses but very weak against tensile stresses. Steel rebar is placed inside concrete members to support the tensile stresses as shown in Figure 9.9. At this point in your engineering career it is good practice to report both the maximum tensile and compressive stresses at each critical point on the beam.

.jpg)

9.2 Beam Design for Bending

Click to expand

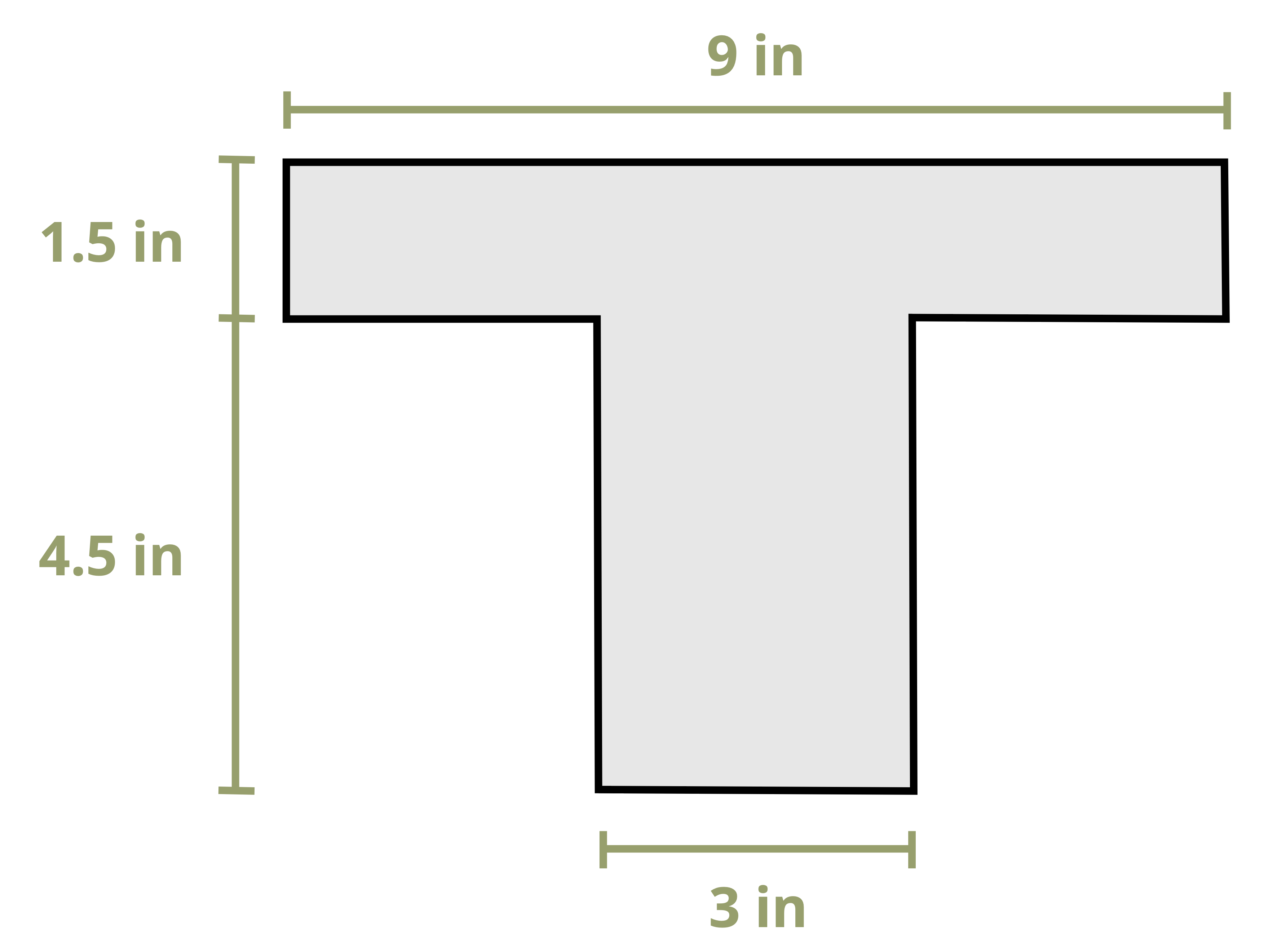

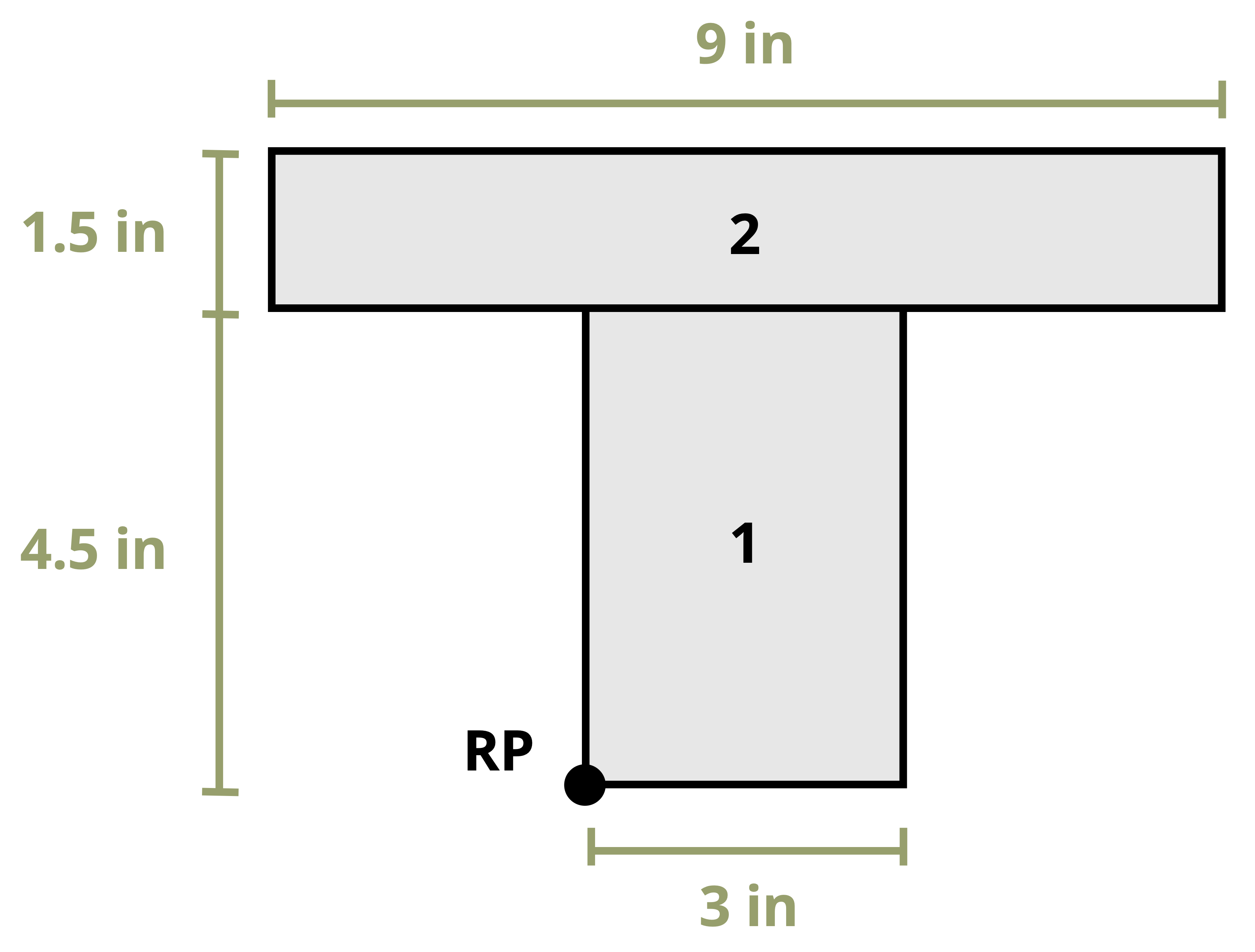

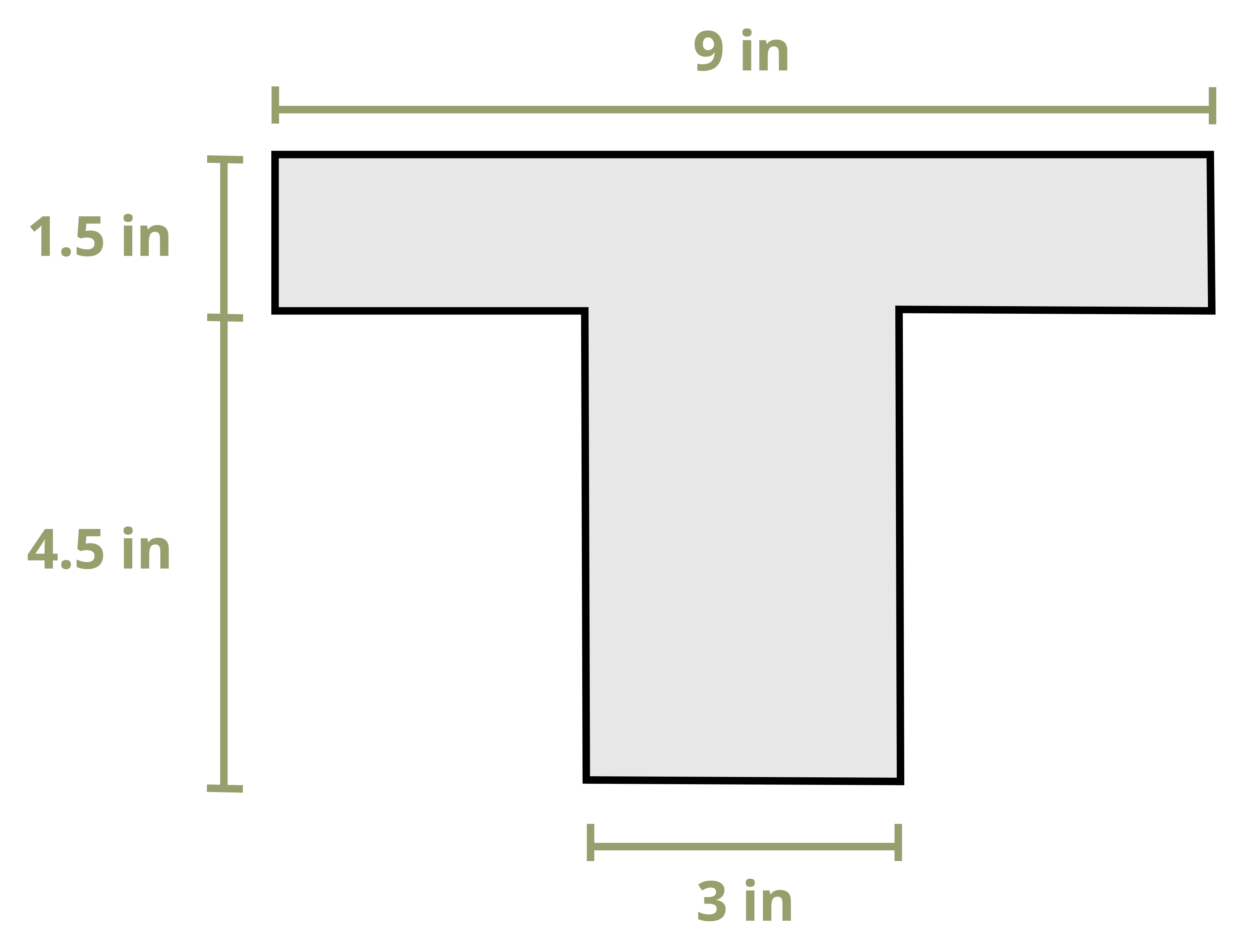

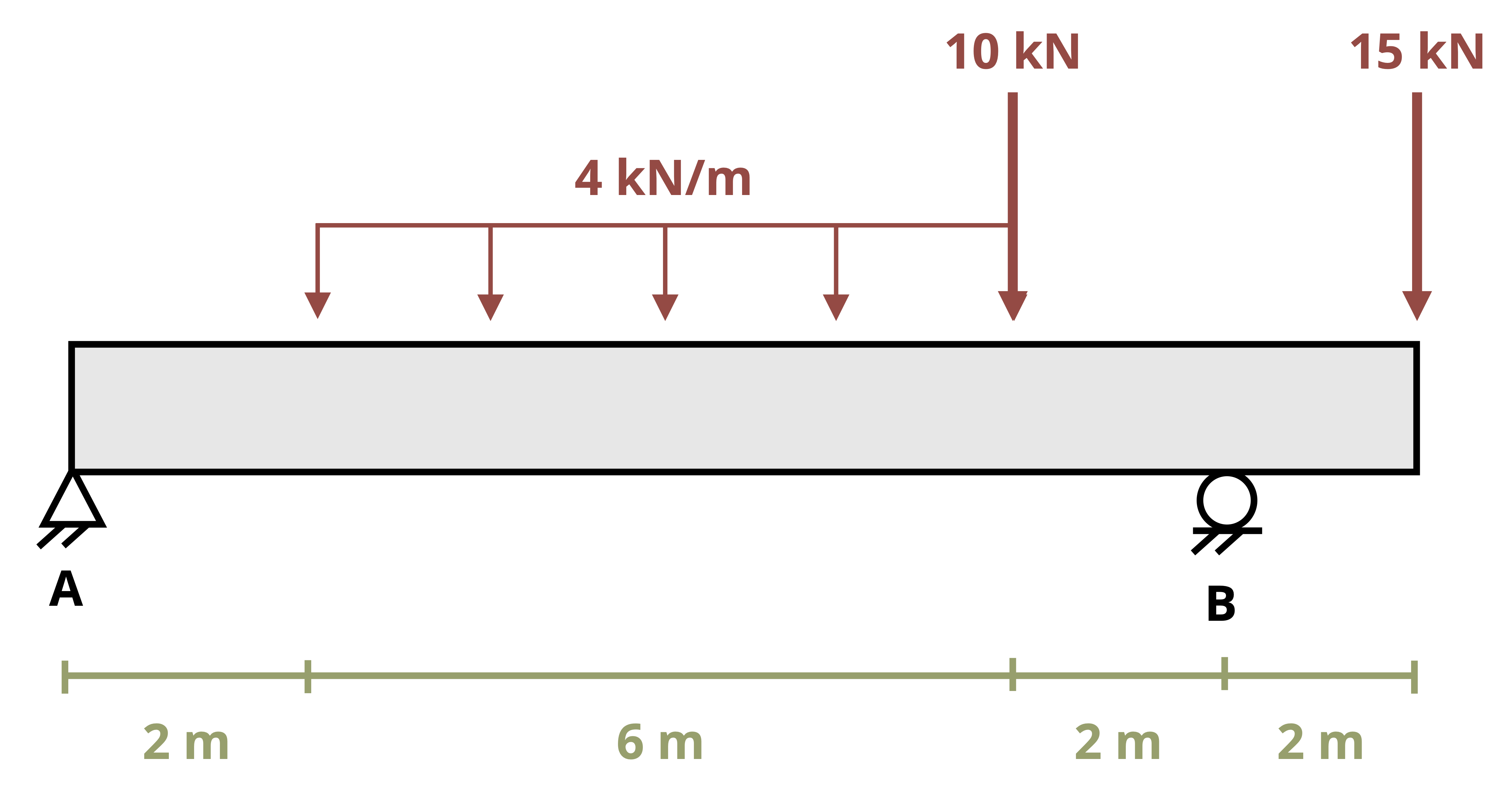

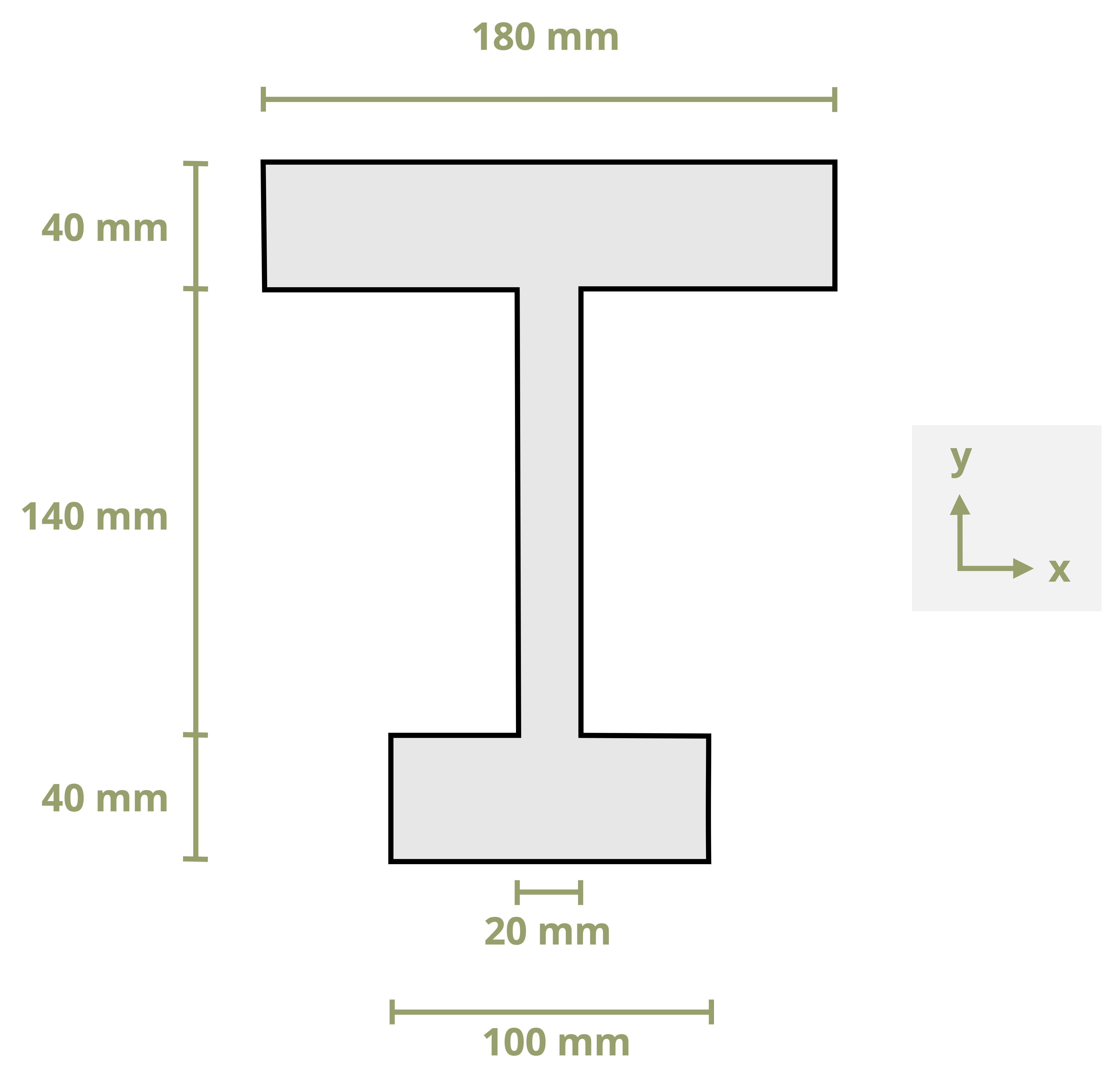

Frequently beam design is governed by the bending moment. This section leverages your understanding of bending stress to design two common categories of beams capable of withstanding their applied internal moments. This section starts with rolled steel beams of varying cross sections. Appendix A provides a sampling of these standard shapes. Then follows a discussion of rectangular cross-sections, which are common for timber beams.

A safe design requires that the allowable stress of the material used is greater than the stress due to the loading. The flexure equation for maximum bending stress, \(\sigma_m=\frac{M_{\max } c}{I}\), has four variables: σm, Mmax, c, and I. We’ll start with the allowable stress of the material, σall, and use the |Mmax| derived from the loading condition. What is left are section properties, I, and c. For standard shapes these are combined into one variable, section modulus (S).

\[ \boxed{S=\frac{I}{c}} \tag{9.3}\]

We can substitute this value into the flexure formula and rearrange for Smin, which is the minimum allowable value of the section modulus for the beam.

\[ \boxed{S_{min}=\frac{\left|M_{\max}\right|}{\sigma_{allow}}}\text{ ,} \tag{9.4}\]

Smin = Minimum required section modulus for a beam to resist the bending stress [m3, in.3]

|Mmax| = Magnitude of the maximum internal bending moment [N·m, lb·in.]

𝜎allow = Maximum allowable stress for the beam [Pa, psi]

9.2.1 Design of Standard Steel Sections

As long as the beam is designed such that its section modulus is larger than Smin, the beam is guaranteed not to fail due to bending stress. Rolled steel beams tend to have relatively complex cross-sections with multiple dimensions that can be varied to alter a beam’s section modulus and therefore its resistance to bending stress. Designing each dimension individually would be time consuming and it would be costly to manufacture a unique beam for every loading condition.

Instead, beams are mass produced in standard sizes and engineers simply select the most appropriate beam for their specific need. Thus many safe standard steel shapes are available to satisfy this equation. Engineering is determining which of the shapes that work you will use. Often you will need to consider many criteria.

In this section we use cost to determine the shape. Steel beams are priced by their weight, and the higher the weight, the more expensive. To choose the most economical shape, we have selected the shape with the smallest weight (i.e., smallest cross-sectional area).

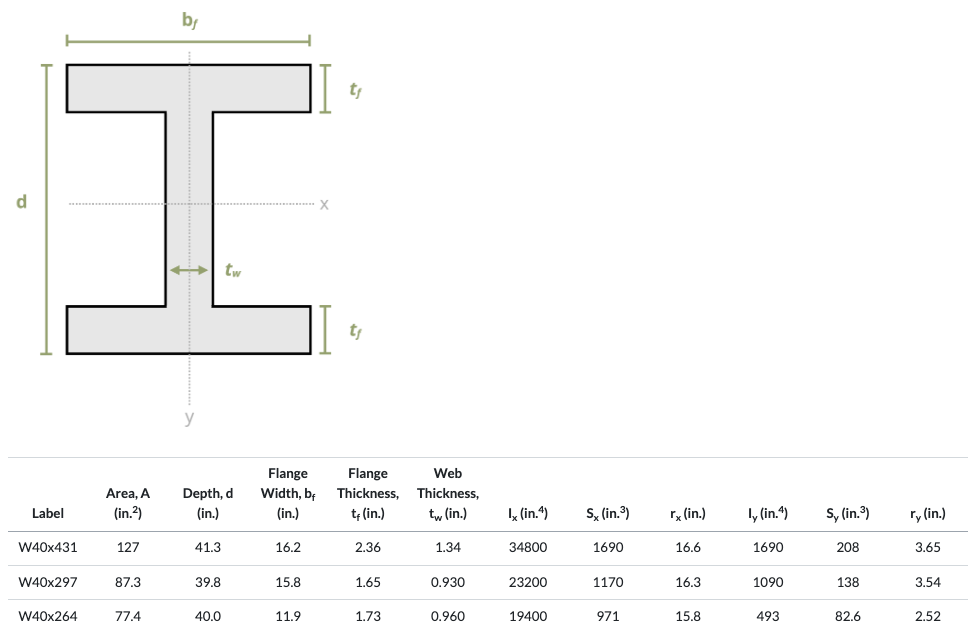

Basic structural steel shapes have standardized cross sectional dimensions. W shapes (standing for wide flange) are often used for beam design because they have an efficient cross section. Figure 9.10 is a sample of the beam table in Appendix A.

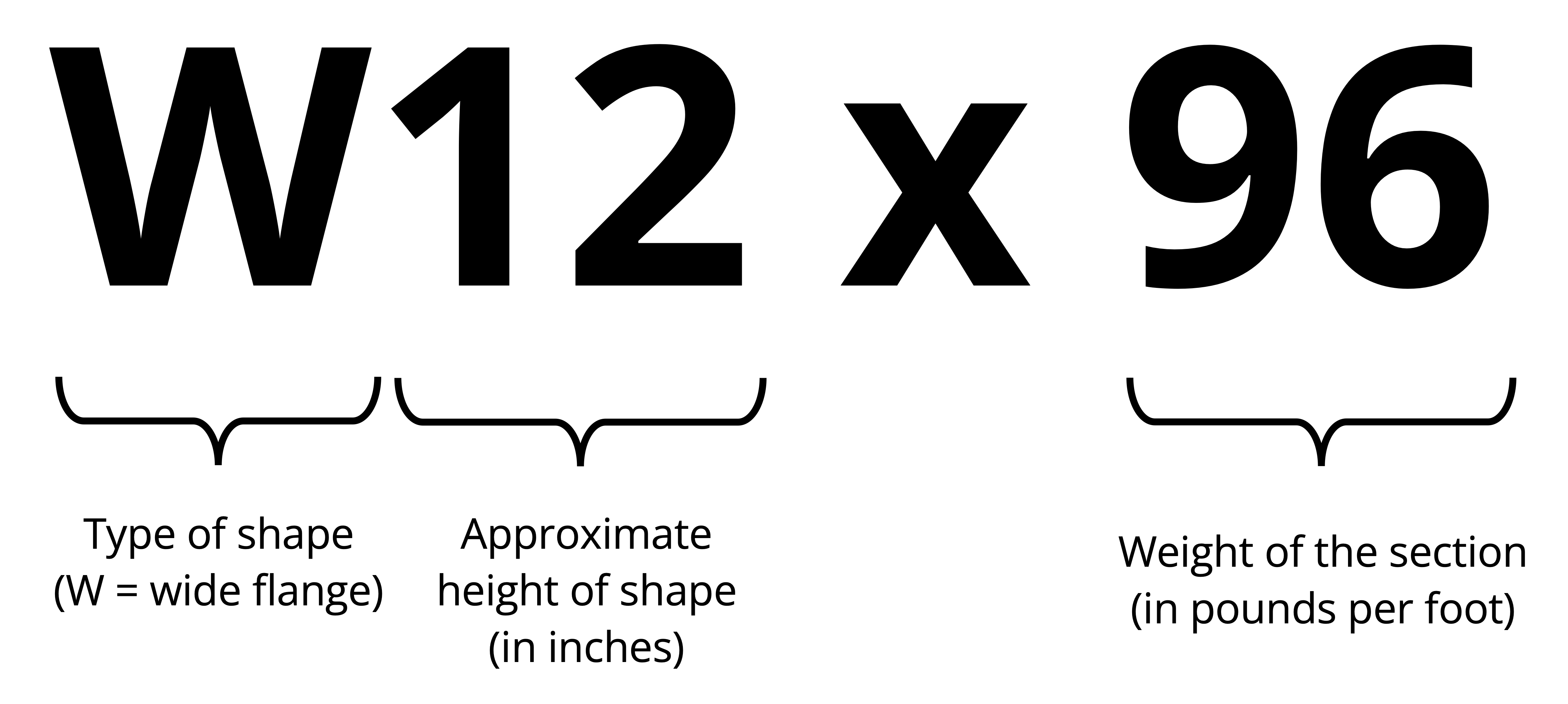

Each beam has a designation that quickly gives us information about the section (see Figure 9.11).

Notice in the sample beam section table in Figure 9.10 that all are W shapes and grouped by approximate height (first number). Within each height grouping the shapes are arranged from lightest to heaviest (second number) when going from the bottom to top of the height grouping. Given for each standard shape in this table are the cross-sectional area, depth (height), flange and web dimensions, second moment of area in the x and y directions, section modulus in the x and y direction, and radius of gyration in the x and y directions (last is a geometric property related to buckling, used in Chapter 15).

In certain instances the selection of a section might be constrained by such factors as the permissible depth of the cross-section or the allowable deflection of the beam. Here the discussion is limited to materials that behave the same in tension and compression. If this is not the case (e.g., when using concrete), then you may need to check multiple points along the length of the beam. Additionally, if the section is not symmetric about the neutral axis, the maximum tensile and compressive stresses may not occur at the chosen place on the beam. Note that this procedure considers only bending stresses. Although bending stresses do control the design of most beams, there are instances where shear or deflection will be in control. Chapter 11 discusses this topic further.

Example 9.3 designs a wide-flange beam to resist bending stress.

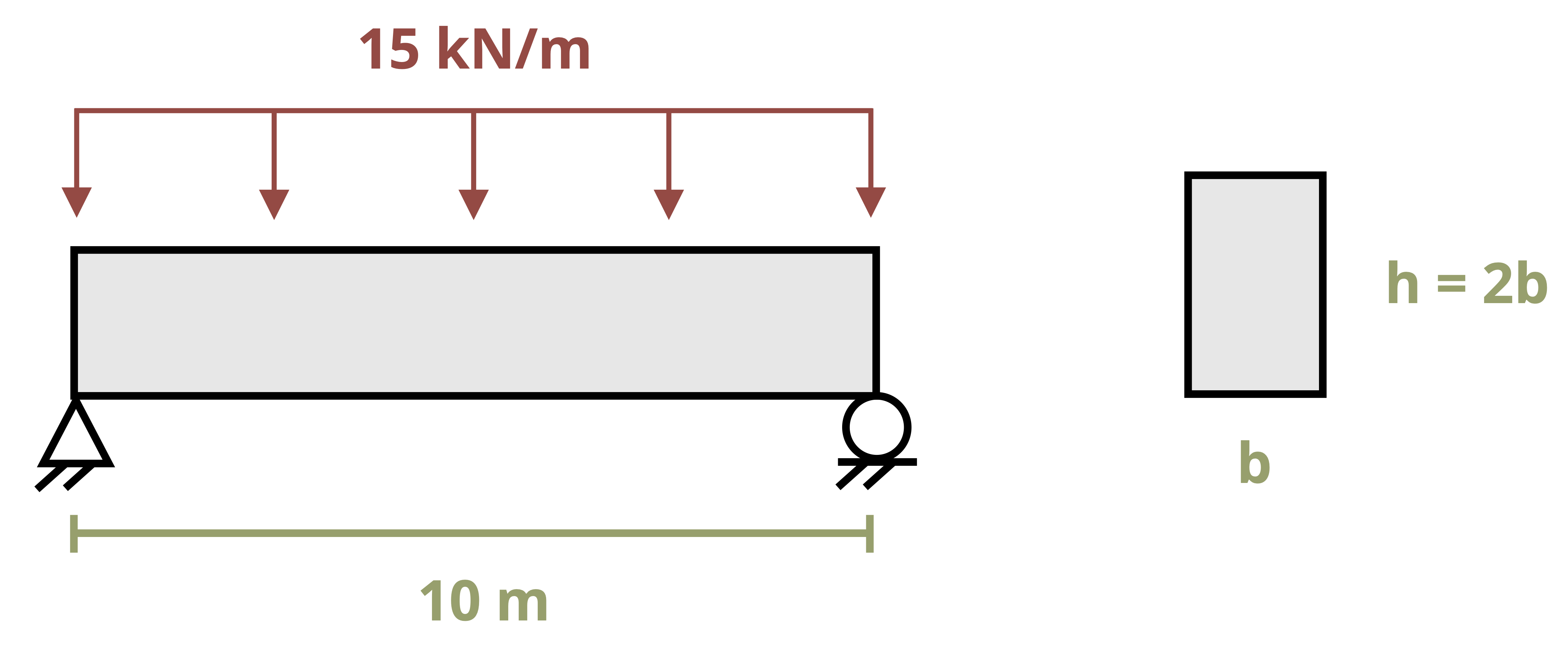

9.2.2 Design of Rectangular Sections

Rectangular cross-sections are common for timber beams. Only two dimensions need to be specified, base and height. While there are standard rectangular cross-sections too (e.g., 2” x 4”), we’ll approach the design of rectangular cross-sections by assuming that one dimension scales with the other, and so we need to specify only a single dimension. Rather than select from a list of standard cross-sections, we’ll specify this required dimension exactly.

Calculate the minimum section modulus as before.

\[ S_{min}=\frac{\left|M_{max}\right|}{\sigma_{allow}} \]

Now set this value:

\[ S_{min}=\frac{I}{c} \]

For a rectangle, calculate

\[ \begin{gathered} I=\frac{b h^3}{12} \\ c=\frac{h}{2} \end{gathered} \]

So the resulting equation is

\[ S_{min}=\frac{I}{c}=\frac{2 b h^3}{12 h}=\frac{b h^2}{6} \]

Problems will be set up such that there is a relationship between b and h, which leaves only one unknown that can be solved for directly. This will be the minimum acceptable size for this dimension—anything larger than the calculated value will not fail due to bending stress.

Example 9.4 designs a wooden beam with a rectangular cross-section to resist bending stress.

For the purposes of this text it is appropriate to give exact answers to three significant figures. In practice we wouldn’t generally specify the required dimension down to the mm since this is unnecessarily precise to manufacture. It is more practical to design to perhaps the nearest 10 mm, remembering to always round up. For example, we calculated the required dimension b = 153 mm. We must not round this down to 150 mm because this is below the required value, but rounding up to 160 mm would be acceptable. While not included in this problem, a factor of safety (Section 4.8) is included in all designs in practice.

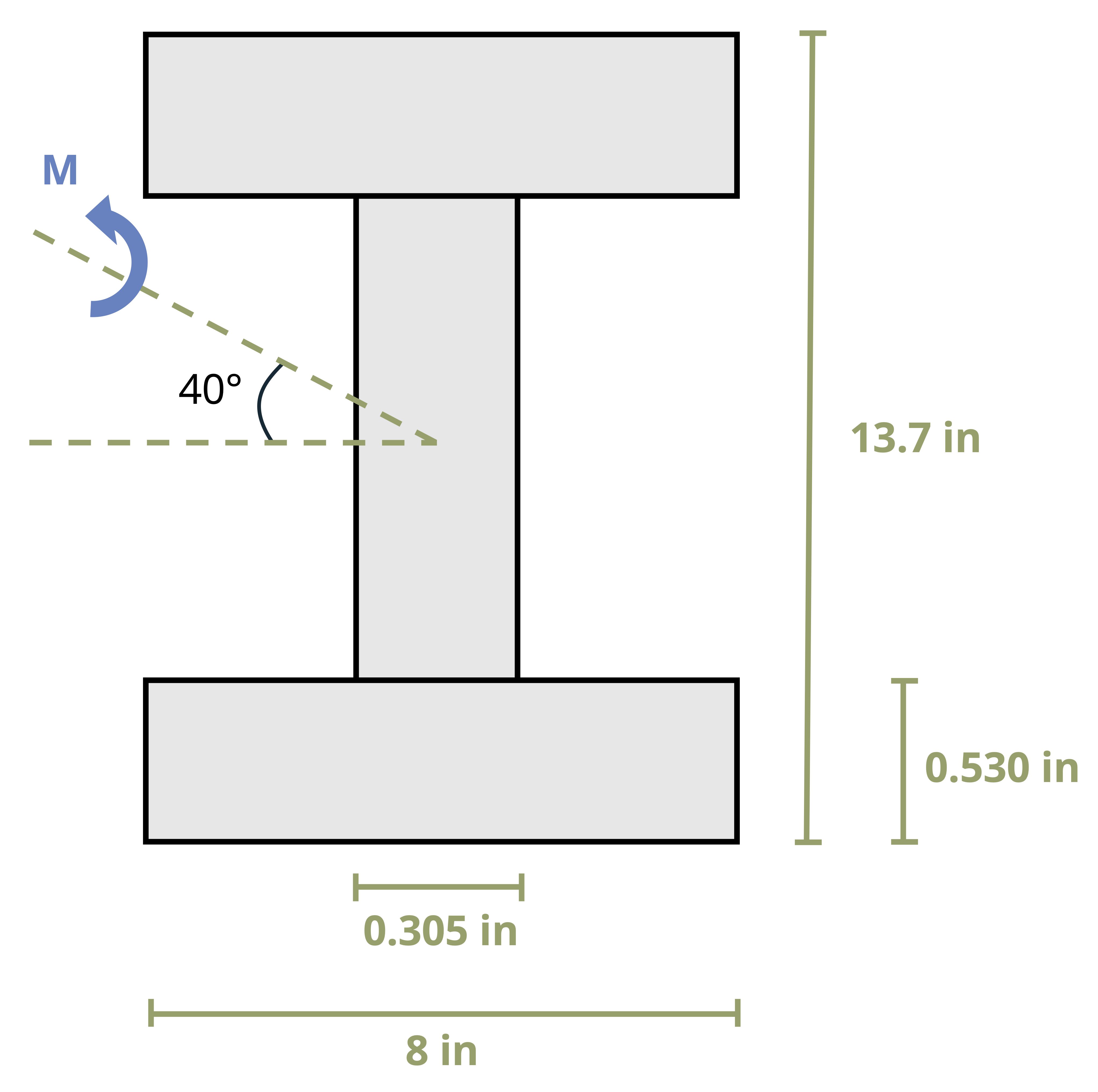

9.3 Unsymmetric Bending—Moment Arbitrarily Applied

Click to expand

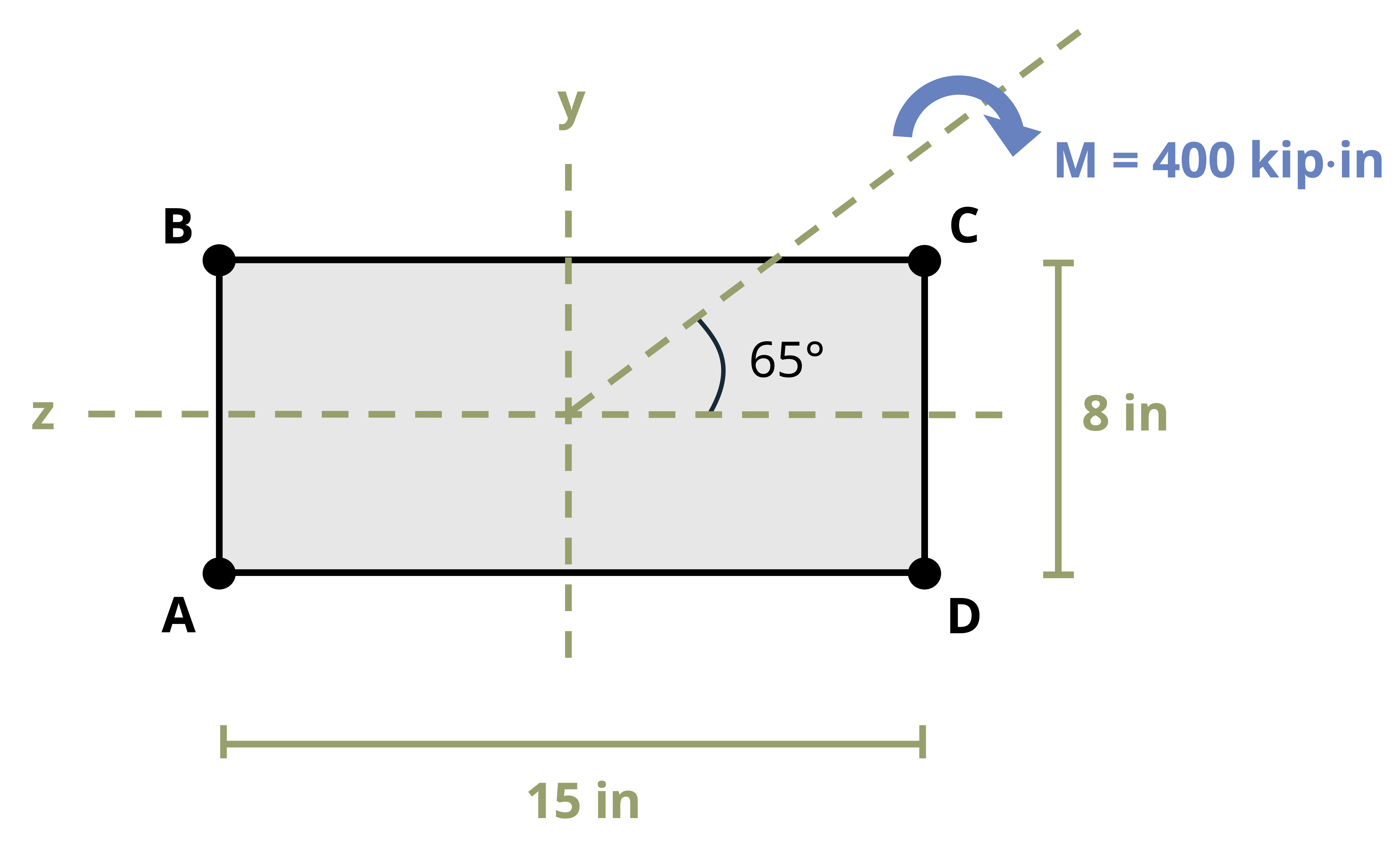

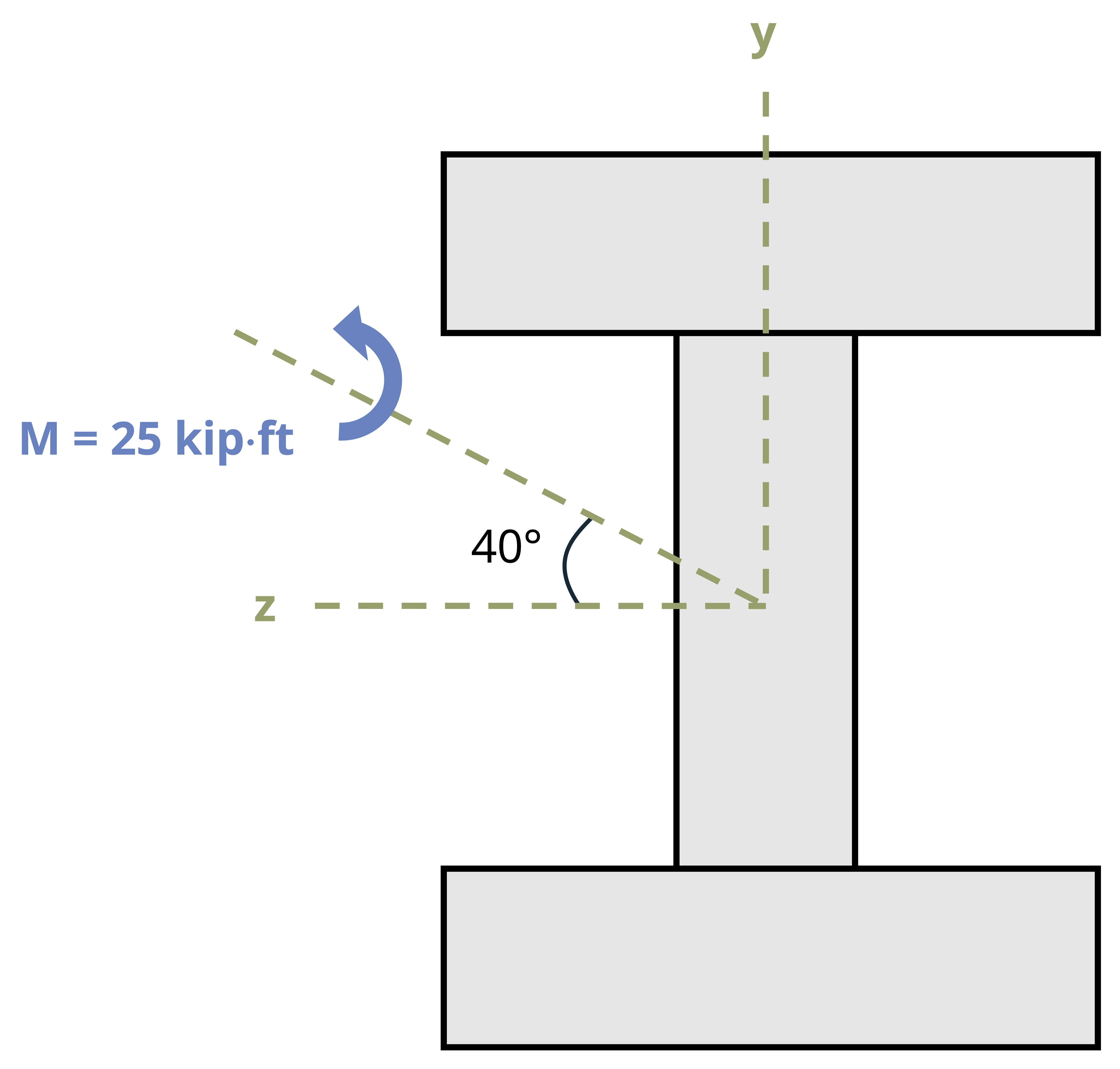

Occasionally a member may experience loading where the bending moment, M, doesn’t align with one of the cross-section’s principal axes. In such cases it is advisable to initially resolve the moment into components along the principal axes. The flexure formula can subsequently be applied to ascertain the normal stress induced by each moment component. Finally, employing the principle of superposition helps us determine the resultant normal stress at the specific point.

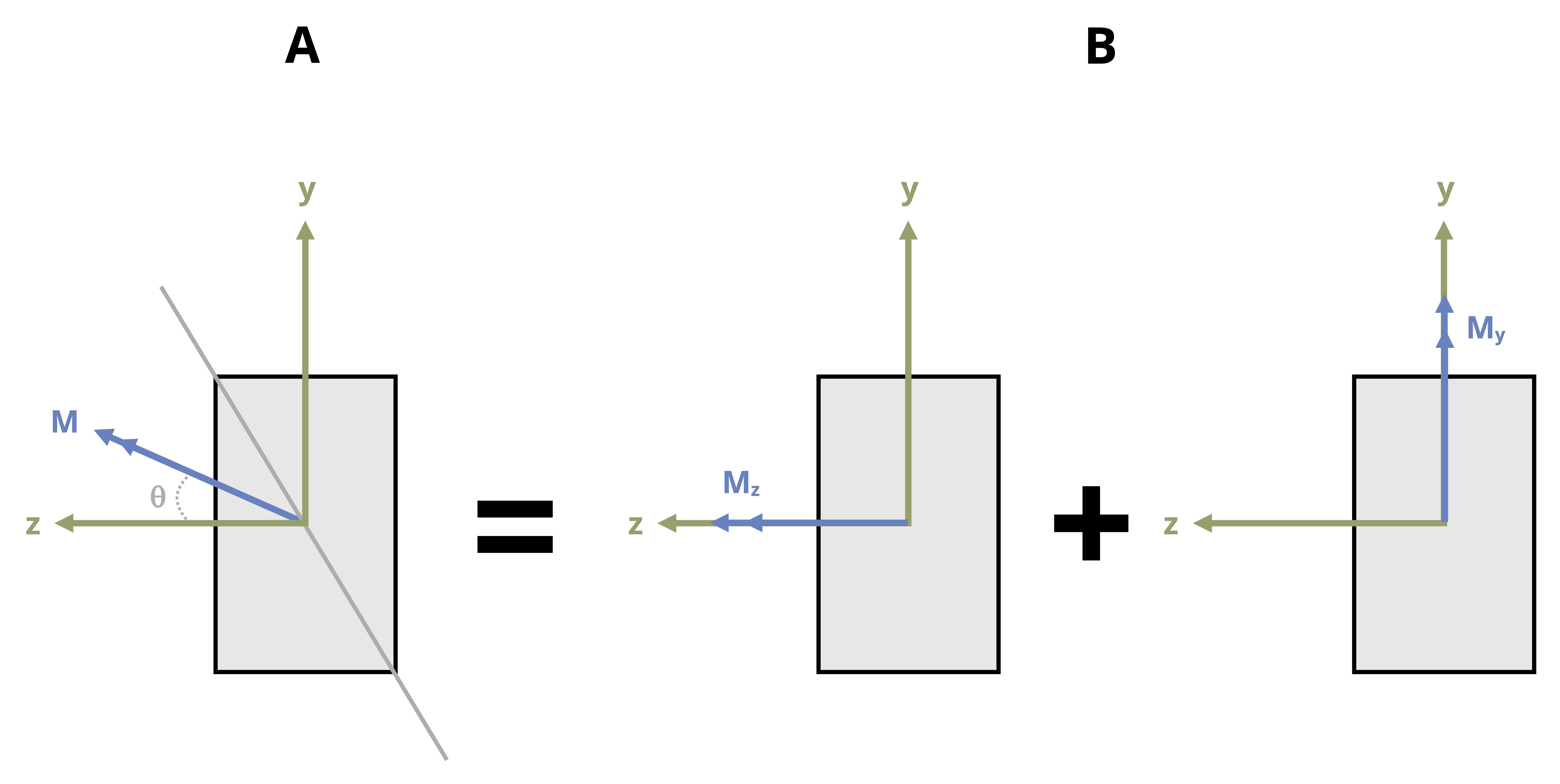

To systematize this process, envision a beam with a rectangular cross-section subjected to a moment, M, as depicted in Figure 9.12 (A). Here M forms an angle, θ, with the maximum principal z-axis, which is the axis of maximum second moment of area for the cross-section. It is assumed that θ is positive when directed from the positive z-axis toward the positive y-axis. We can resolve M into y and z components.

\[ \begin{aligned} & M_z=M \cos \theta \\ & M_y=M \sin \theta \end{aligned} \]

Figure 9.12 (B) shows the components of M acting on the rectangular cross section. It’s important to keep track of which side of the beam is in compression and which is tension when subjected to both Mz and My. Here we’ll use tensile stress as positive and compressive stress as negative. Looking at a +Mz shows us that this moment causes the top of the section to be in compression and the bottom of the section to be in tension. Inspecting the section when subjected to +My reveals that the left side will be in tension whereas the right side will be in compression. Combining what we know about the sign convention with the flexure formula, we can calculate the resultant normal stress at any point on the cross section by using the following equation:

\[ \boxed{\sigma=-\frac{M_z y}{I_z}+\frac{M_y z}{I_y}}\text{ ,} \tag{9.5}\]

𝜎 = Bending stress at point of interest [Pa, psi]

Mz, My = Internal bending moment components about the z-axis and the y-axis [N·m, lb·in.]

y, z = Distance in the y and z directions from the centroid to the point of interest [m, in.]

Iz, Iy = Second moment of area about the centroidal z-axis and y-axis [m4, in.4]

Note that for the signs to work correctly we must assign the appropriate sign to the y and z values and to the components of the bending moment. These values are measured from the coordinate system that originates at the centroid where the x-axis is coming out of the page. It’s also possible to ignore all the signs and use your spatial awareness to determine if each term is in tension or compression due to the applied moment.

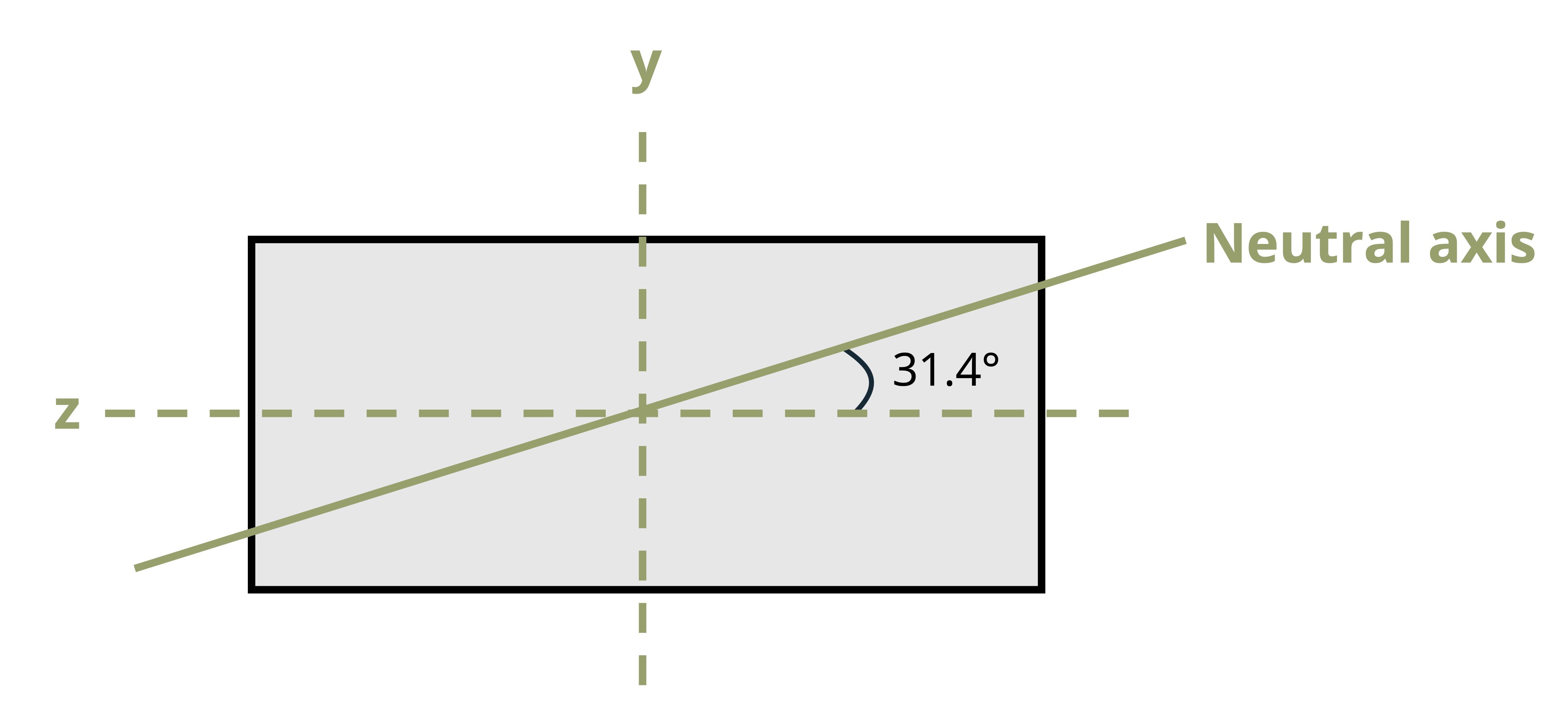

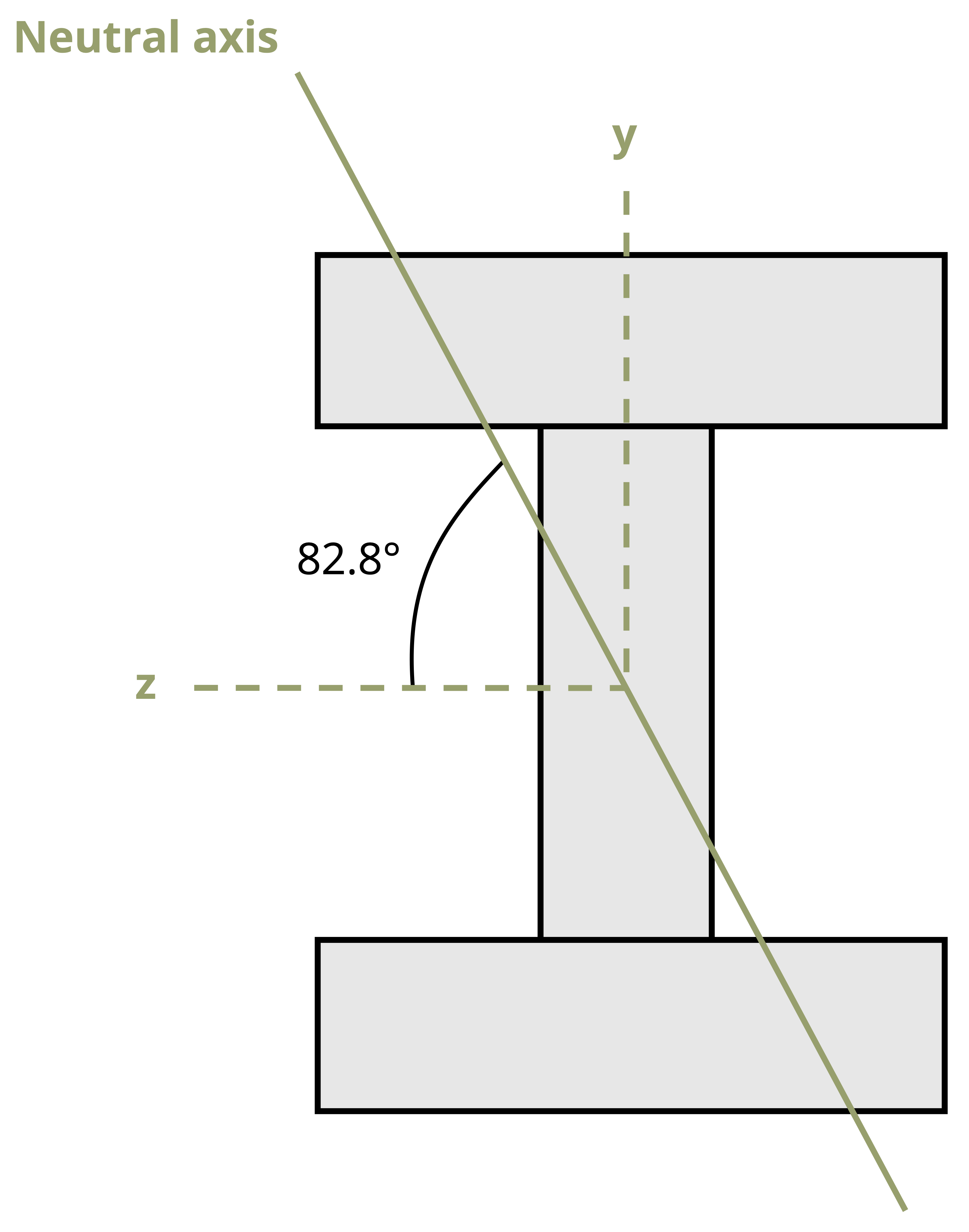

Previously we identified the neutral axis—a line marking points of zero stress. When the bending moment acted around the horizontal axis, the neutral axis was also horizontal and passed through the centroid of the cross-section. When the bending moment acts at an angle (θ) from the horizontal axis, the neutral axis will pass through the centroid but will not be horizontal. It too will be at an angle (α).

Let’s now determine the orientation of the neutral axis, as this will commonly not coincide with the axis of bending moment.

Derive the orientation of the neutral axis by setting the previous normal stress equation equal to zero.

\[ 0=-\frac{M_z y}{I_z}+\frac{M_y z}{I_y} \]

Then rearrange this to solve for y.

\[ y=\frac{M_y I_z}{M_z I_y} z \]

Now put this equation in terms of M by using \(M_z=M \cos \theta\) and \(M_y=M \sin \theta\).

\[ y=\left(\frac{I_z}{I_y} \tan \theta\right) z \]

Since the slope of the line is \(\tan \alpha=y / z\), where the angle α represents the angle the neutral axis forms with the z-axis, this can be written as:

\[ \boxed{tan(\alpha)=\left(\frac{I_z}{I_y}tan~\theta\right)}\text{ ,} \tag{9.6}\]

𝛼 = Orientation of the neutral axis, measured from the z-axis [\(^\circ\), rad]

𝜃 = Orientation of the internal bending moment, measured from the z-axis [\(^\circ\), rad]

Iz, Iy = Second moment of area about the centroidal z-axis and y-axis [m4, in.4]

Example 9.5 and Example 9.6 demonstrate how to calculate bending stress at various points on a cross-section when the moment is arbitrarily applied.

Summary

Click to expand

References

Click to expand

Figures

All figures in this chapter were created by Kindred Grey in 2025 and released under a CC BY license, except for

Figure 9.1: Looking up at bridge beams used to support a landscaped bicycle and pedestrian bridge in Seattle. Washington State Dept of Transportation. 2023. CC BY-NC-ND. https://flic.kr/p/2ojECo3.

Figure 9.4: The distortion of a kid’s toy when undergoing bending. Steve Berry. 2006. CC BY-NC-SA. https://flic.kr/p/4EzyRy.

Figure 9.5: Column failure due to bending. Joshua Miller. 2005. CC BY-NC-ND. https://flic.kr/p/5RLNx.

Figure 9.9: The end of the prestressed concrete beam showing the prestressing steel and rebar. Mike Sheinin. 2009. All rights reserved. Used under fair use. https://flic.kr/p/6BW5sA.